One afternoon in 2011, I hurried toward the harbor of my island, Fuvahmulah. The day was clear and bright, the kind that sharpens the colors of sea and stone. I went with my closest friend, Mohamed Shujau—known to everyone as Mod—to see whether reef fish were moving along the harbor edge.

We climbed onto the massive boulders that form the harbor’s protective barrier, stones stacked against the open ocean. It was high tide. Waves crashed relentlessly against the rock faces, sending white spray into the air. When we reached the top, we found two other friends fishing below for blue-spotted dartfish. They told us their lines had been cut several times and that bluefin trevally were already working the reef.

Improvisation is second nature to island fishermen. Mod and I walked to a nearby shop and bought 30-pound monofilament line, which I wound carefully around an empty cooking-oil plastic bottle—about 90 meters in total. I picked up standard hooks, likely size 13 or 14. At the fish market, there was no shortage of bait. I quickly removed a tuna’s spleen, stomach, and intestines, rigging the intestine first so it would hold on the hook longer once submerged.

I cast the line and let the waves and current carry the bait toward the center of the reef flat. The response was immediate. Strikes came quickly, and I landed two bluefin trevallies in succession. Then I noticed something different—movement close to the rocks, just below where I stood.

Standing on a boulder about five feet above the water, I dropped the bait almost straight down. Below, the seabed was sandy, with open gaps between the rocks. When the bait reached the bottom, the line tightened with a long, steady pull. I tested it gently, then struck hard. The bite was unlike that of a trevally. This fish swallowed the bait and dragged the line but did not explode into a run.

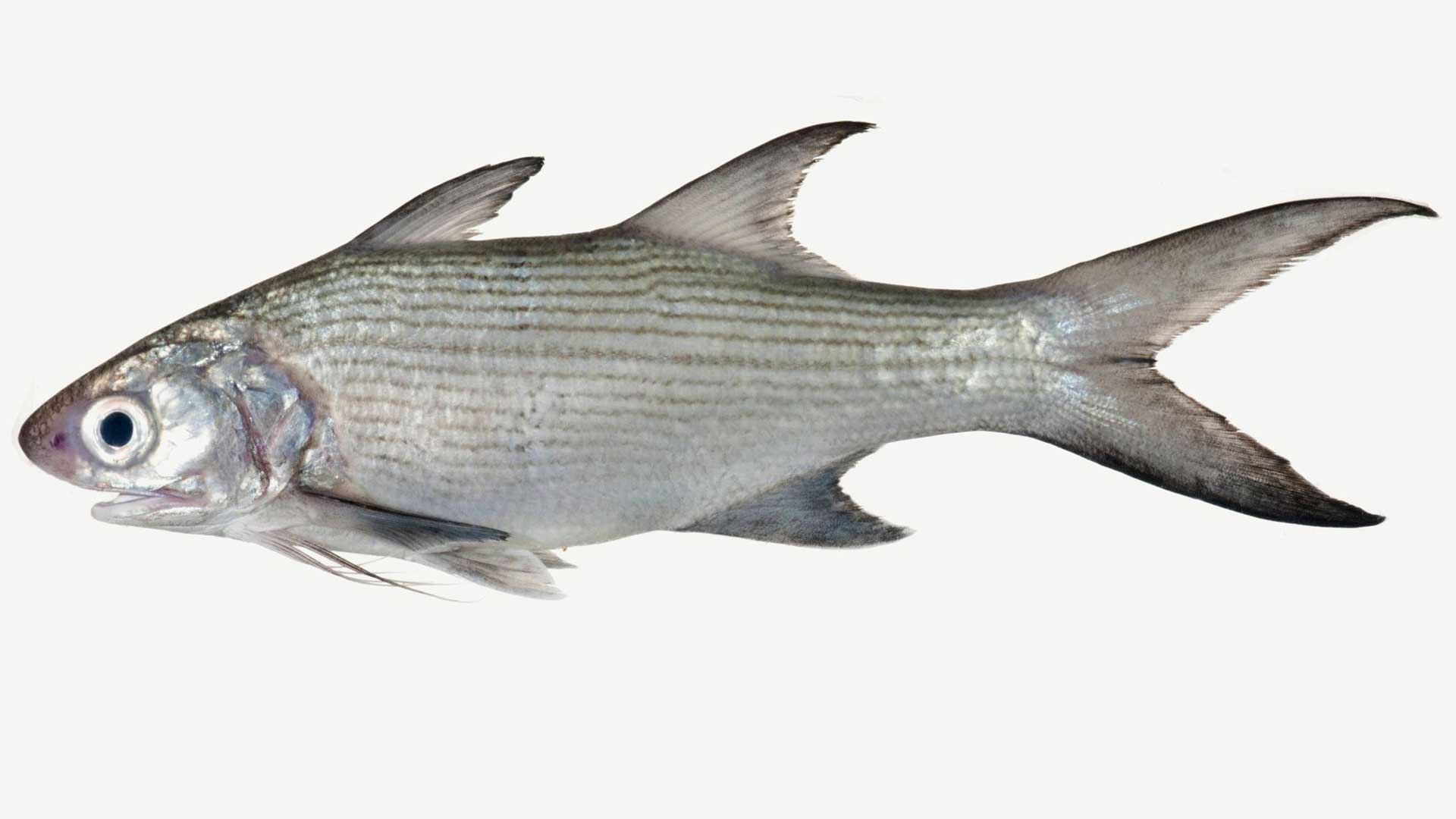

I hauled it up quickly. It was a six-finger threadfin—Keylamaha, as we call it locally. Within the next 15 minutes, I landed five of them, each around 18 inches long.

Later, I was reminded of what Ahamadhubea, a mudhim at our district mosque, once told me: the best time to catch keylamaha is in the evenings around the full moon. In earlier days, fishermen baited their hooks with hermit crabs—baroala—rigged carefully through the belly and bound with fine thread. They often fished at Thoondu Beach, using long poles—sometimes up to 14 feet—to land the fish across the wide shoreline.

Although six-finger threadfin favor sandy beaches, they are equally at home along rocky edges. The harbor of Fuvahmulah is one such place. That afternoon, the sea was rough, waves hammering the boulders without pause—and the keylamaha seemed to thrive in the turbulence. Feeding mainly on crustaceans such as shrimp, crabs, and worms, as well as small fish and other benthic invertebrates, they are well adapted to chaotic water. Even soft silicone lures can provoke strikes.

The reef flat beside the harbor is almost always restless. Large waves crash into the rocks, creating a hazardous but productive fishing ground. It is also prime territory for giant trevallies. Landing fish here—whether trevally, giant trevally, or six-finger threadfin—is difficult and often dangerous.

We usually fish from rocks positioned five to fifteen feet above the water. When a fish is hooked, we must quickly move down to lower boulders, timing our steps between waves, to prevent the line from snagging on coral. The foam is thick, the footing uncertain. Lines frequently tangle, and every descent carries risk.

Once, a massive wave swept my friend Thambi and me into deep holes between the rocks. We were lucky. When the water drained away, we climbed out shaken but unharmed. The danger is real—but so is the pull of the experience.

That day at the harbor, I landed a strong mix of trevallies and six-finger threadfin. More than the catch, it was the setting—the pounding waves, the living reef beneath our feet, and the constant negotiation between risk and reward—that stayed with me. On Fuvahmulah, fishing is never just about fish. It is about reading the sea, trusting instinct, and standing, quite literally, at the edge of the ocean’s power.