This is a series of articles I’ve chosen to publish under the title “Diver’s Len.” The purpose of these articles is to present photographs and videos captured by photographers and divers that provide scientific insights into the species.

The photographer or diver has granted permission for the publication of the photos and videos in these articles. Furthermore, we publish additional informative and scientific descriptions with the photographer’s or diver’s permission.

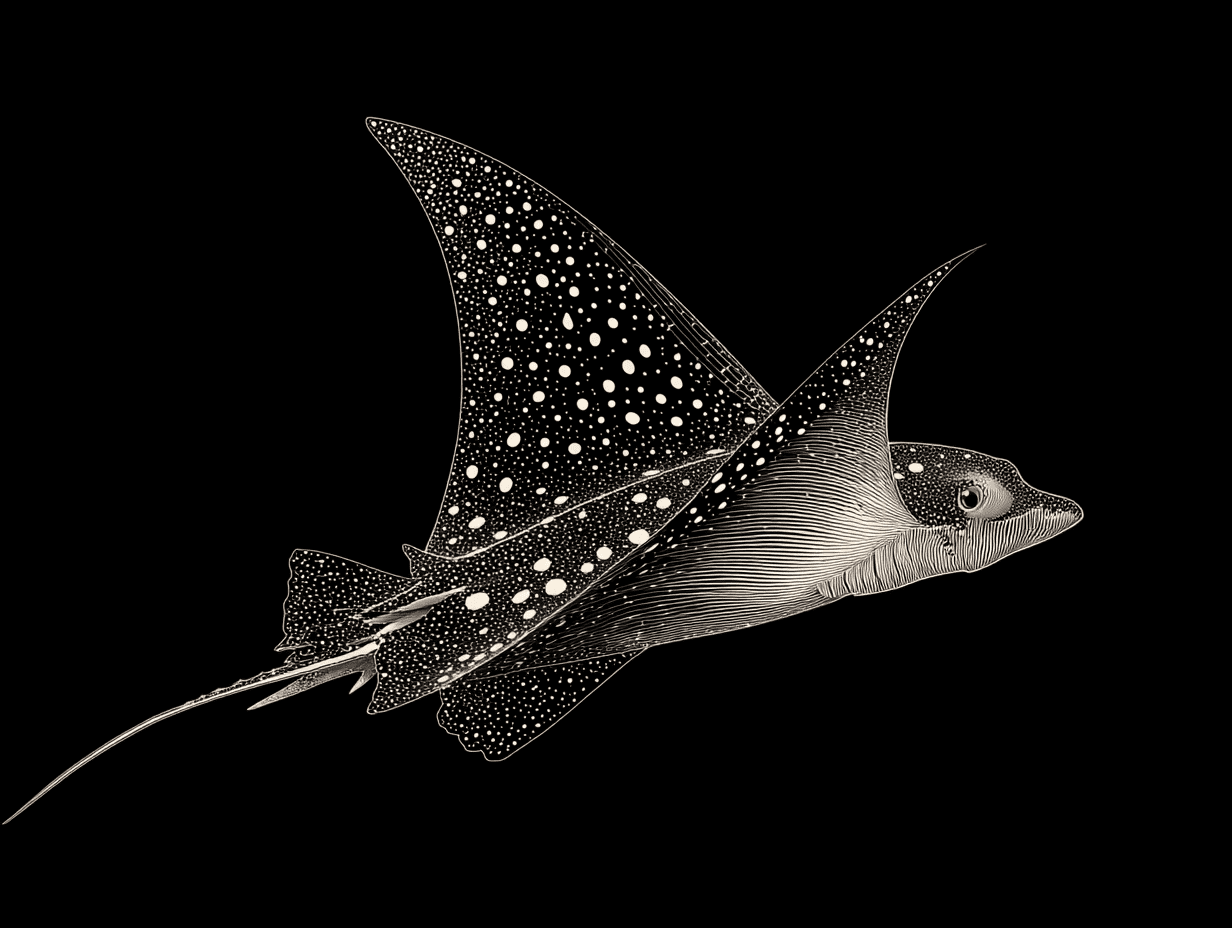

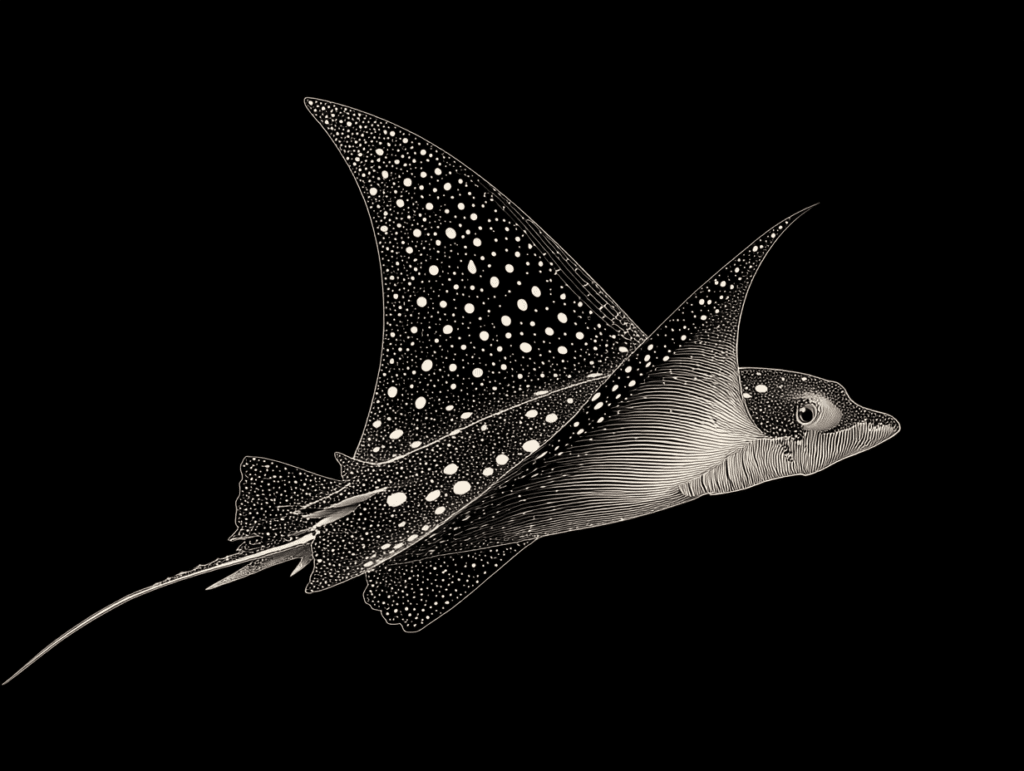

COMMON NAME: Spotted Eagle Ray

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Aetobatus narinari

ECOSYSTEM/HABITAT: Live on soft bottom

ORDER: Myliobatiformes

FAMILY: Myliobatidae

GENUS: Aetobatus

SPECIES: narinari

The white spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari) is locally known as vaifiya madi. This graceful, swift swimmer often forms enormous schools near the surface or much above the bottom, and it is sometimes observed leaping far into the air. In the afternoon, it likes open water and goes to the bottom to feed, mostly on big sand flats that are between the beach and reefs.

To protect its disc, it has a small dorsal fin near the base of a very long, whip-like tail that is 2.5 to 3.0 times the width of the disc when it is not hurt. Just behind the dorsal fin, there are one or more poisonous spines. This species has a maximum width of 3 metres. And its tail can grow to five meters long.

The duck-like nose digs into the sand to find food, which it then breaks up with its strong, plate-shaped teeth. Eagle rays eat clams, whelks, oysters, and crabs.

Eagle rays, which inhabit shallow water near bays and coral reefs, have white spots on their bodies. Most of the time, they live about 80 meters below the surface. They seem to be in schools. But they spend most of their time out in the open water.

They have recently been divided into three groups: the Pacific white-spotted eagle ray (A. laticeps) inhabits the East Pacific, the ocellated eagle ray (A. ocellatus) inhabits the Indo-Pacific, and the true spotted eagle ray (A. narinari) inhabits the Atlantic.

The tides influence their movement. They are also more active at high tide. Usually, we find them in large groups or schools, but we have also seen them alone in shallow water.

In the Maldives, we are fortunate enough to encounter groups of roughly 20 of them.

To find out more about the behaviour, movement, and habitat use of white-spotted eagle rays, researchers from Florida Atlantic University’s Harbour Branch Oceanographic Institute carried out a study in 2020.

Researchers used acoustic telemetry and transmitters with unique codes. The study found that they use it during the day and at night when the water is shallower. In the ocean and lagoons, they move faster. For the most part, they move slowly in these places.

Eagle rays may spend more time in the shallow water of the lagoon at night than they do during the day, according to the research.

Understanding the use of channels is crucial for evaluating risks and potentially devising strategies to safeguard the white-spotted eagle ray from adverse effects.

According to Breanna DeGroot, M.S., lead author, research technician, and former graduate student working with Matt Ajemian, Ph.D., co-author and assistant research professor at FAU’s Harbour Branch, “Both channel and inlet habitats receive a lot of human activity, such as boating and fishing, and are vulnerable to coastal development impacts from dredging.”

Moreover, cooler and darker conditions caused rays to move to deeper depths, whereas warmer and lighter conditions caused them to spend more time in the channels and inlets. The temperature significantly increased the rate of movement, indicating that warmer temperatures are more conducive to ray activity.