Catching sea creatures is exciting and requires skill, but it can also be extremely dangerous. Even catching a fish weighing 5 to 15 kg can result in tragedy. Many fishermen in the Maldives had dangerous encounters, such as falling into the sea after an unexpected line entangled their arms or hands, as well as numerous bodily injuries while fishing and landing fish. This story tells how our forefathers caught tiger sharks in Maldivian waters – the most dangerous fishing in the Maldives.

The term for fishing tiger sharks is ‘maa keyolhu kan’. This tradition is thought to have originated hundreds of years ago. The primary goal of catching these large predators was to maintain dhoni and bokkura, which are wooden vessels used for fishing and travel throughout the Maldives’ islands. The tiger shark’s large liver produces oil that can be used as a preservative on these types of vessels. Prior to the ban on shark fishing in the Maldives, some fishermen used fish waste to attract sharks. Some fishermen even managed to reel in these predators by utilising nothing more than fish heads and waste. However, in the traditional method of fishing for these large predators, our forefathers used turtles, manta rays, and octopuses. They caught a harpooned dolphin and stored it for a day or two to allow the bait to rot.

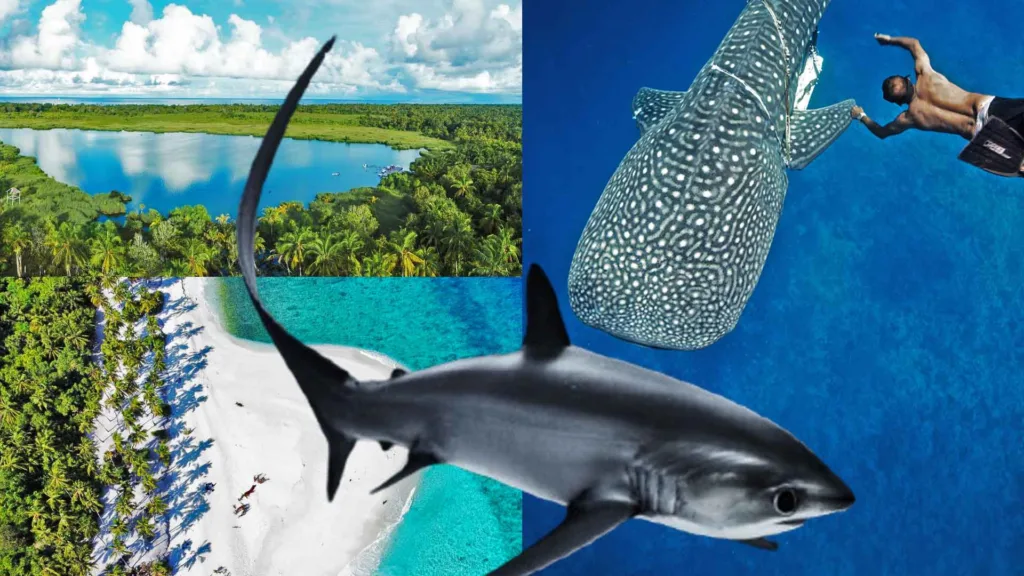

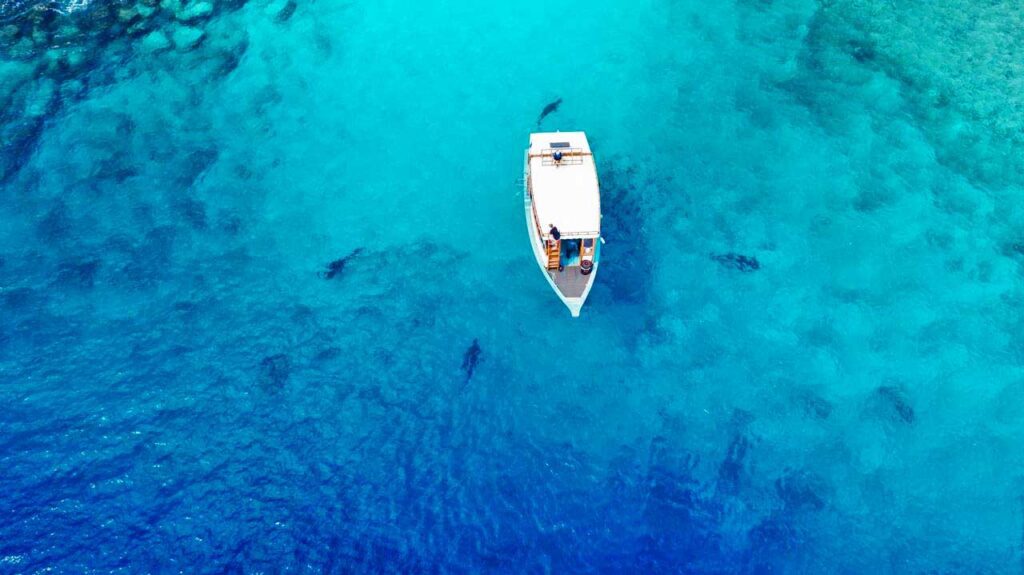

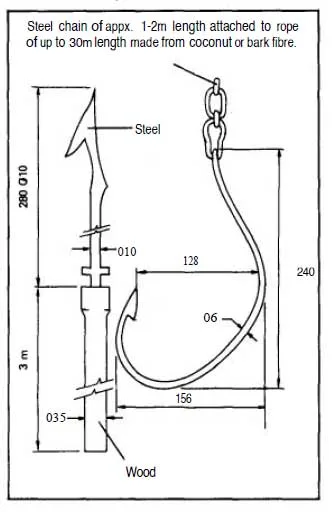

Tiger sharks were fished with traditional fishing boats known as ‘masdhoni’ and ‘vadhu dhaoni’. There were designated spots for fishing for this predator on many atolls. The majority of these areas had strong currents near channels (kandu). This method was also used outside the atolls because tiger sharks prefer relatively deep waters; our fishermen were able to target them in those areas. The fishing boat hung the rotten bait from it, so blood and other gross stuff slowly leaked into the water. Heavy harpoons and huge iron hooks with chain leaders were used by the expert fishermen when the shark was drawn to the bait and rose to the surface. Typically, they harpooned tiger sharks ranging in length from 2 to 4 meters. Traditional fishermen reported that 6-metre-long tiger sharks were occasionally harpooned.

This method carries significant risk. When the tiger shark became attracted to the bait and swam near the dhoani, the fishermen thrust the harpoon at it, which impaled it just behind the head, in the upper back region, and near the pectoral fins. However, if the shot strikes the predator at an incorrect location, it can drag the fisherman overboard. Fishermen came across some sharks that flipped over easily and are thought to be strong spirits, so they decided not to harpoon any more on the day.

There had been incidents involving towing people and dhoanis. Line entanglement around limbs and the body has resulted in fatal drownings and other bodily injuries. Crew members sustained serious injuries as a result of heavy gear punctures. Some people believed that tiger sharks and other large ocean creatures like whales and sharks were spirits. Before venturing out to sea to catch tiger sharks, fishermen sought assistance from ‘fanditha verin’, who were well-known for performing local sorcery. Master sorcerers perform rituals involving fanditha charms and spells to ward off bad luck when harpooning tiger sharks.

People believed that failure to follow the rituals would result in a harpooned shark returning as a monster or spirit. After harpooning, they cleaned the dhoani with shark blood to avoid misfortune. Some fishermen believed that seeing tiger sharks and whale sharks on the water’s surface while fishing was a sign of bad luck or a negative omen that would prevent them from catching anything. They also believed that observing this behaviour in front of the dhoani was a terrible omen. The fanditha masters also offered coconuts and fish to the sea as rituals, and the fishermen were instructed to pray. They also use incense smoke to recite fanditha spells. They also used lunar phases to determine the best time to catch even the largest predators. Some fanditha masters wrote fanditha spells on coconut leaves and distributed them to the fishermen.