Promethean escolar, known locally as Kattelhi, is one of the most special fish found in the deep waters around Fuvahmulah. Even today, many visitors are surprised to learn how deeply connected this fish once was to island life. Long before modern gear and shiny metal jigs arrived in the Maldives, going out to catch Kattelhi was a demanding journey—one that began on land, long before the first oar touched the water.

Fishing as a Way of Life

In those early days, fishing was not simply a profession; it was a rhythm woven into the lives of the people. Every Kattelhi trip required preparation, teamwork, and a strong understanding of the sea. On Fuvahmulah, nothing about this process was easy. From the moment the crew decided they were going fishing, a long list of tasks had to be completed before the bokkura—the traditional wooden vessel—could be launched.

Gathering the Essential Fibre: Vaanaa

The first job was always connected to the land. Fishermen needed to collect vaanaa, thin natural fibre taken from the sea hibiscus tree (dhigai). This fibre played a central role in the fishing setup. With no factory-made ropes or synthetic lines, these hand-cut fibres were used to tie the hook to the main fishing line and to secure the heavy stones that would later be lowered to the seabed.

Cutting vaanaa required patience. The men stripped the bark in careful motions, peeling out fine strands that would later be twisted and strengthened. Even this early step carried a sense of purpose, because everyone knew how important each fibre would be once the boat reached deep sea.

The Hardest Task: Breaking Coral Stones

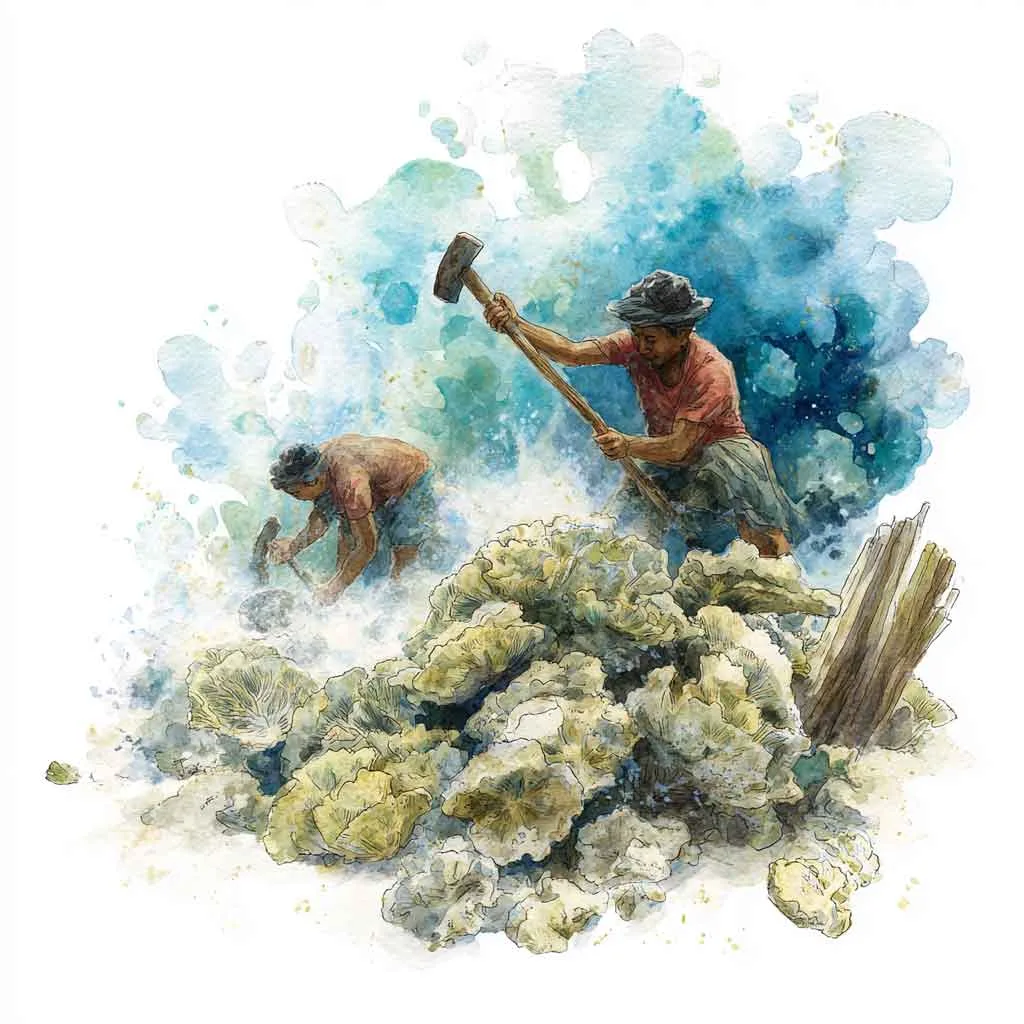

But the most physically demanding task was breaking sand corals. In those days, fishermen used large coral stones as weights to carry the baited hook deep into the ocean. These stones had to be broken into pieces weighing at least 3 to 4 kilograms—heavy enough to sink fast, but manageable enough for the crew to handle on a rocking boat.

The chief fisherman of the bokkuraa, known respectfully as the Keyoulhu, always decided how many coral stones were needed. Most trips required smashing around 80 pieces.

Securing the Only Hammer in the Ward

Once the number was set, the Keyoulhu assigned two men to the job. Their first challenge was simply securing the right tool. There was only one “saudharaatha marotheyli”, a special 6-kilogram hammer, in the entire Dhadimago ward. It belonged to the Abeage household, and fishermen had to go there early to book it. The rule was clear: first-come, first-served. If another crew had booked the hammer first, the whole fishing plan had to be delayed.

Breaking the Corals on the Shore

Once the hammer was in their hands, the two men hurried to the beach where the big sand corals lay scattered along the shoreline. They worked under the sun, swinging the heavy hammer again and again until the large coral blocks broke apart. Each piece had to meet the required weight, so every strike was measured and intentional. When the pieces were ready, they carried them in a mudeyshi, a handwoven coconut-leaf bucket, to the location where the bokkuraa waited.

Preparing the Crew and the Boat

Only after these tasks were completed could the crew prepare to leave. A traditional Kattelhi fishing trip used a team of five to eight men. Four of them—including the Keyoulhu—handled the fishing line. One man steered the rear oars, known as the Dhekedefaali. Another tied the vaanaa fibre to each coral stone, securing it firmly.

At the centre of the boat sat two rowers working the bandofaali, the two main oars attached to the sides of the vessel. Between these rowers, one tied the coral stones onto the line, while the other removed the hook once a fish was caught.

Natural Bait and Traditional Methods

For bait, fishermen relied on nature. Flying fish were a favourite, but reef fish such as groupers were also commonly used. They threaded the hook through the bait at least twice, always leaving the sharp point exposed. The method was simple but effective.

Fishing the Deep: How Kattelhi Was Caught

Once they reached the fishing grounds, the coral stone was released into the water. It sank rapidly, dragging the hook down with it until it touched the seafloor. Then the fishermen tugged the line sharply to free it from the stone.

After that, the real work began. By jerking and shaking the fishing line in steady rhythms, they attracted the Kattelhi lurking in the deep. These fish were strong and fast, and catching even a single one took skill and timing. But in those days, a successful trip often brought in 50 to 100 Kattelhi per bokkuraa.

From Tradition to Modern Jigging

Today, modern jigging has replaced these old methods. Metal jigs and advanced rods have made the process easier and more efficient. But the story of Kattelhi fishing—the teamwork, the preparation, the deep respect for the ocean—remains an important part of Fuvahmulah’s heritage.

A Living Connection to the Island’s Past

For visitors exploring Fuvahmulah, this history offers a beautiful glimpse into the bond between our people and the sea that has shaped our lives for generations. These fishing methods were shared by Hussain, a reef fisherman from the Udharesge household in Dhadimago Ward.