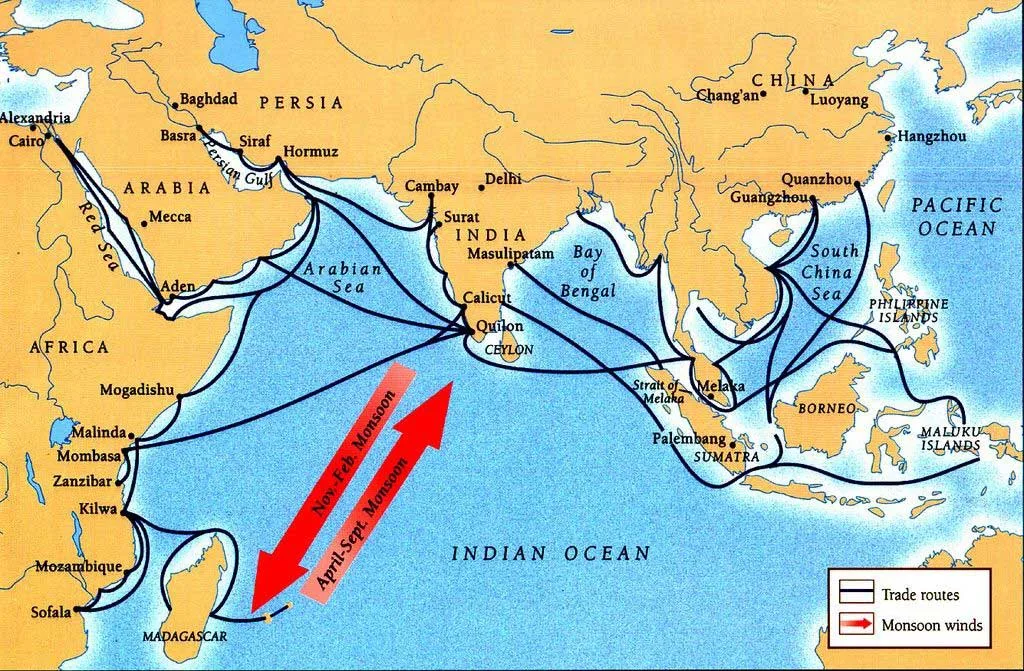

Scattered across the heart of the Indian Ocean, the Maldives has never been isolated by water. Instead, the sea has always been its greatest connection to the wider world. Long before charts, engines, or instruments, Maldivians crossed vast distances guided by winds, stars, and experience. Trade voyages, shipwrecks, and accidental landfalls shaped island life, leaving behind stories that still echo through generations.

A Nation Born of the Sea

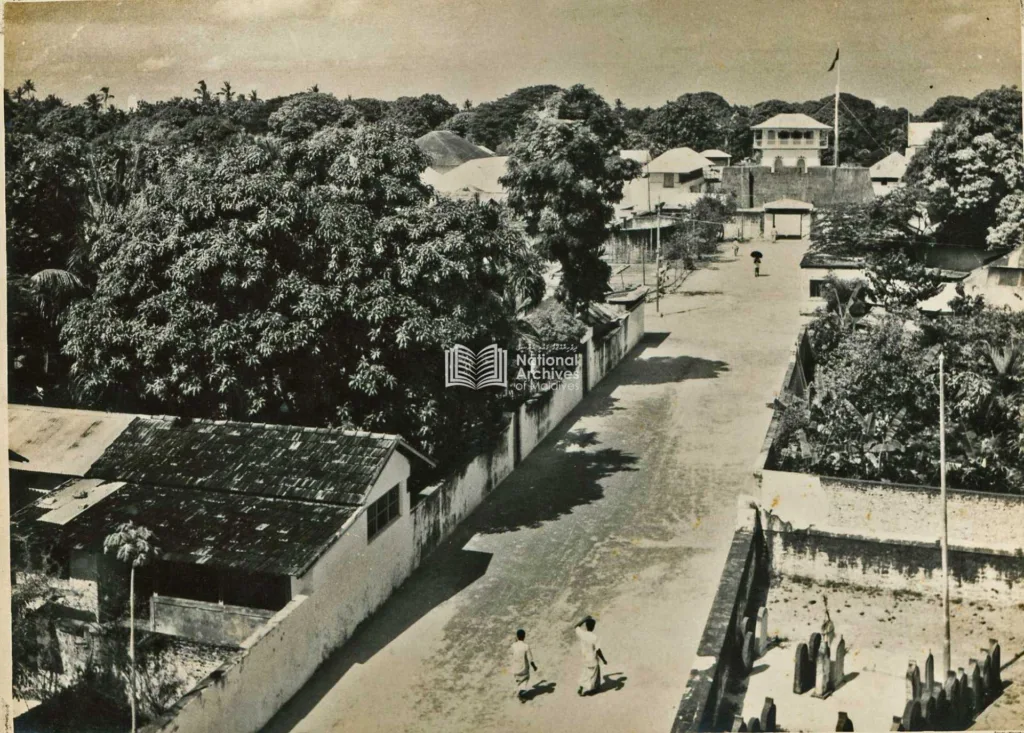

Life in the Maldives depended on maritime trade. With no metals, clay, or timber of their own, islanders relied on exchange with distant lands. Heavy wooden vessels known as oḍi, veḍi, and later dhoani carried dried tuna, coconut products, rope, and sweets to South India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). In return came rice, iron, pottery, cloth, and tools essential for survival.

These were not short coastal trips. Maldivian sailors often ventured directly into open ocean, timing their departures with the monsoon winds. The sea was dangerous, but familiarity bred confidence, and generations of knowledge turned wide waters into navigable routes.

The Fear of Missing Home

The return journey was often the most perilous. The Maldives is low-lying and difficult to spot, especially at night. Sailors feared missing the islands entirely—slipping through wide channels without realizing it and sailing on into open horizon.

Stories passed down through families describe boats drifting for days or weeks, crews scanning the sea in mounting anxiety. Some eventually reached distant shores by chance. Others vanished without trace, leaving behind only unanswered questions and quiet remembrance.

Shipwrecks and Unintended Landfalls

When vessels were blown off course, they sometimes landed far from home—on remote islands or foreign coasts across the Indian Ocean. Survival often came at a cost. Cargo was lost, months passed in unfamiliar ports, and the long journey back left families with little more than stories of endurance.

Shipwrecks became part of island memory, retold as cautionary tales and reminders of the sea’s power. Each story reinforced respect for the ocean and the need for patience, preparation, and humility.

Castaways and Remarkable Escapes

Among the most extraordinary accounts are those of castaways who survived against overwhelming odds. Boats carried far south by wind and current sometimes reached uninhabited islands, where sailors faced hunger, isolation, and uncertainty.

In rare cases, ingenuity saved lives. One well-known story tells of stranded sailors tying messages to the legs of frigate birds, which migrate north toward the Maldives. When one such message was found, a rescue followed—a rare return from what would otherwise have been certain disappearance.

Reading the Sea

Traditional Maldivian navigation relied on observation rather than instruments. Sailors read the sea through stars, cloud formations, wave patterns, currents, bird movements, and subtle changes in water color. Knowledge was passed orally, refined through experience, and guarded carefully.

Families waited at home for their loved ones to arrive safely on the island. While waiting in hope for the vessel to arrive safely, if they saw a house snake (nannugathi) or another creature, they said it was a “bavathi,” meaning it was believed to be a sign that something good would happen.

. Songs and poems preserved these anxieties, turning personal fear and hope into shared cultural memory.

An Enduring Maritime Identity

For Maldivians, the ocean was never merely a route or a resource. It was a force that demanded skill and respect. Trade brought survival, but the same waters could erase entire crews without warning. This balance shaped a people defined by caution, cooperation, and deep environmental awareness.

The history of the Maldives is written not only on land, but across the sea. In stories of missed islands, distant shores, and long-awaited returns, the nation reveals itself as one shaped by motion—forever bound to the open ocean that sustained, tested, and defined it.

Editorial Note: This article draws on widely known Maldivian oral history and maritime traditions, as well as information shared by my two late uncles, Ibrahim Didi of Orchidmaage, Fuvahmulah, and Abdulla Rafee of Aabaadhuge, Fuvahmulah, and by my father, Ahmed Salih Hussain.

Ibrahim Didi was a skilled navigator (locally known as a maalimee) who travelled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) aboard my grandfather Hussain Didi’s (Kudubae) veḍi and went on to navigate several Maldivian vessels during his lifetime. Abdulla Rafee and my father also travelled to Ceylon on my grandfather Hussain Didi’s (Kudubae) veḍi.