Scattered like a broken string of pearls across the deep indigo of the central Indian Ocean, the Maldives have always been more than a tropical paradise. Long before honeymooners arrived by seaplane, these low-lying atolls marked the difference between survival and catastrophe for sailors who crossed one of the world’s most demanding oceans.

For medieval Arab mariners, the Maldives were both a lifeline—and a graveyard.

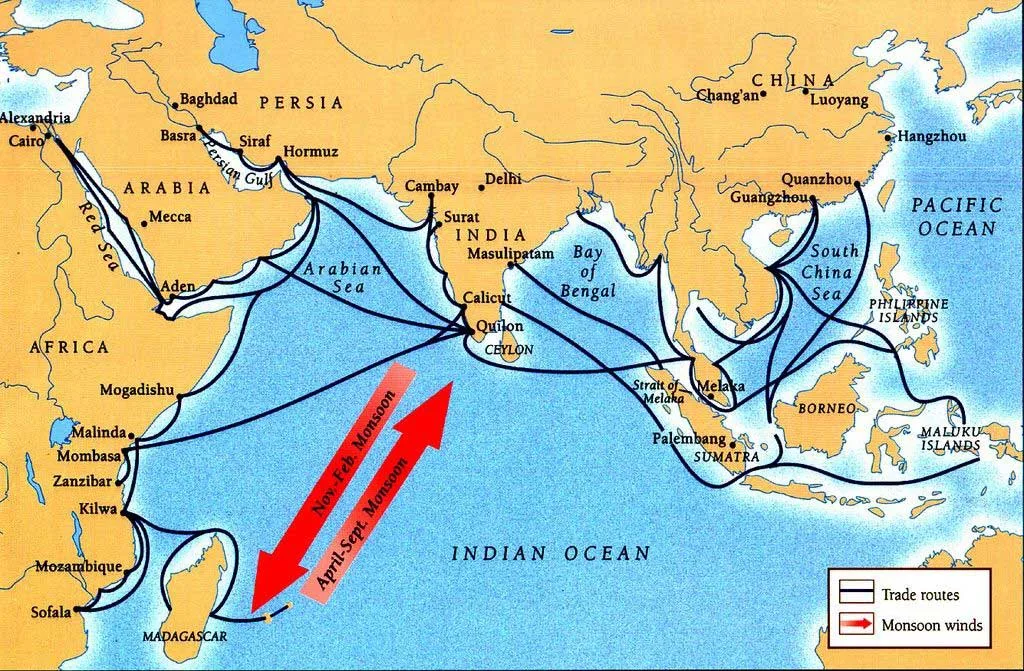

From the ninth century until the dawn of the 16th, the Indian Ocean functioned as an Arab sea. Guided by generations of accumulated knowledge and propelled by the seasonal breathing of the monsoon winds, Muslim navigators stitched together a vast maritime silk road. Their routes linked the Red Sea and East Africa to India, Southeast Asia, and the far edges of the South China Sea, moving spices, textiles, ceramics, and ideas across thousands of miles of open water.

The Perilous Pitstop

The traditional passage was a brutal test of endurance. Arab dhows struck northeast across the Arabian Sea toward the port of Diu, hugged India’s Malabar Coast, and rounded the dangerous southern tip of Sri Lanka—one of the most treacherous corners of the Indian Ocean.

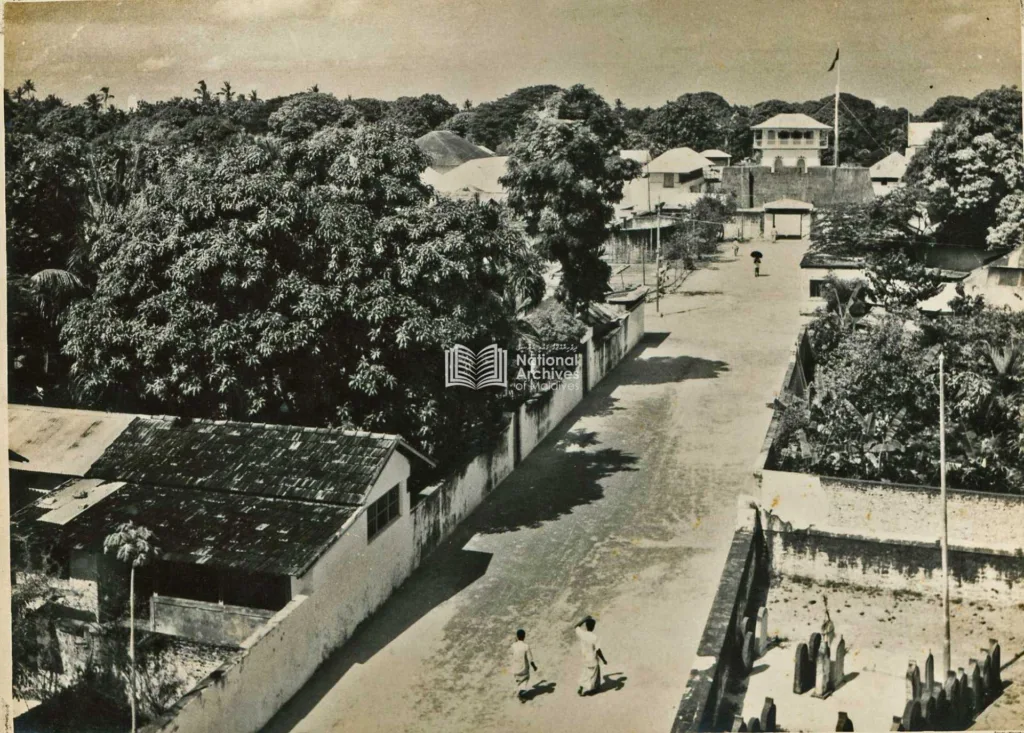

At the heart of this journey lay Malé. Even then, the capital island functioned as a crucial waystation. Here, Muslim traders—known in European records as “Moors”—replenished fresh water and repaired their vessels. They traded in the local currency of the sea: cowrie shells, harvested by the millions from Maldivian reefs and used as money across Africa and South Asia. They also loaded stores of dried Maldivian tuna, a compact, protein-rich food that could endure months in the tropical heat.

The “One and a Half Degree Channel” (Huvadhu Kandu) in the southern Maldives was a formidable natural barrier. Because this stretch of water was so deep and unpredictable, it forced most Arab dhows to remain in the northern atolls. This geographical constraint is what ultimately transformed Malé into the indispensable trade hub of the Indian Ocean.

GEOGRAPHICAL NOTE

The Scholar-Judge of the Atolls

Centuries before European cannons echoed across the reefs, the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta arrived in the Maldives, not as a merchant, but as a luminary of Islamic law. His tenure as a Qadi (Chief Judge) in the 1340s provides a rare, intimate glimpse into the islands’ social fabric during the peak of the Arab maritime era.

While Arab mariners braved the “lethal maze” of the reefs, Ibn Battuta documented the sophisticated civilization that thrived within them:

- A Destination for Scholars: He noted that the Maldives were a prestigious stop for Arab theologians and judges, who were often recruited by the Sultanate to refine the islands’ legal and religious systems.

- The Global Currency: Battuta was the first to extensively document the industrial-scale harvest of cowrie shells. He marveled at how these small shells, harvested from the turquoise lagoons, were exported to Africa and Asia as a primary global currency.

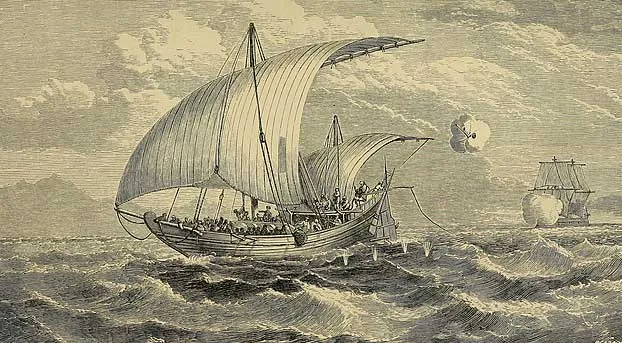

- The “Sewn” Ships: He observed that the traditional Arab dhows were uniquely suited for Maldivian waters; their hulls were “sewn” together with flexible coir (coconut fiber) rather than iron nails, allowing them to survive impacts with sandbanks that would shatter European vessels.

- Cultural Anchors: He recorded the social customs that linked Arab mariners to local families, describing a society that was as welcoming to the pious traveler as it was dangerous to the uninitiated sailor.

“The Maldives are one of the wonders of the world… a place where the islands are small and the people are pious.” — Ibn Battuta, The Rihla (1344)

A Sanctuary from the Cannon

The balance of power shattered in the early 1500s with the arrival of the Portuguese. Armed with heavy cannon and driven by imperial ambition, they sought to choke the spice trade by blockading Indian ports and dominating key maritime chokepoints. The Indian Ocean became a war zone.

This upheaval transformed the Maldives from a quiet supply stop into a strategic refuge.

Arab traders, unwilling to risk interception by European warships, began diverting their routes through the atolls. Portuguese chronicler Duarte Barbosa, both a soldier and a meticulous observer, recorded the desperation of these sailors in the early 16th century:

“Many ships of the Moors which pass from China, Maluco, Peegu, Malaca, Camatra, Benguala and Ceilam, towards the Red Sea touch at these islands to water and take in supplies and other things needful for their voyages. At times they arrive here so battered that they discharge their cargoes and let them go to the bottom. And among these isles many rich vessels of Moors are cast away, which crossing the sea, dare not through dread of our ships finish their voyage of Malabar.”

The choice was stark: risk destruction by cannon fire or gamble on survival among the reefs.

The Legacy Beneath the Waves

Today, the wrecks Barbosa described still lie scattered across the seabed—silent witnesses to a time when the Maldives formed the hidden heart of global commerce. Beneath turquoise lagoons and coral gardens rest ships that carried the wealth of continents and the hopes of men who dared not sail openly.

For centuries, the Maldives represented a calculated risk for Indian Ocean traders: a place of fresh water and safe anchorage, shadowed by the constant threat of shipwreck. Between the crushing weight of the sea and the lethal reach of European guns, the atolls offered one fragile margin of survival.

Paradise, it turns out, has always been perilous.