Early Encounters That Documented Maldivian Society

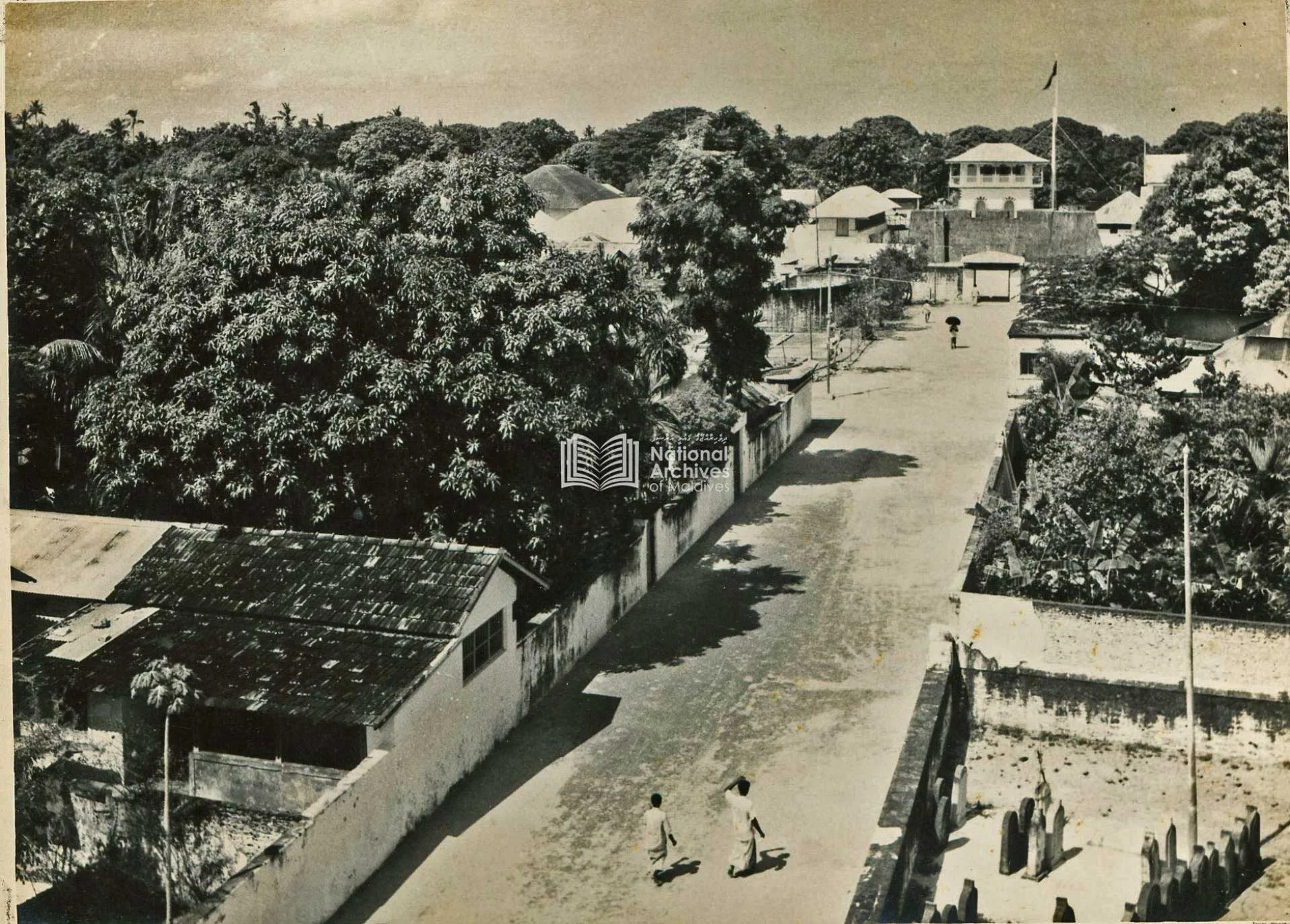

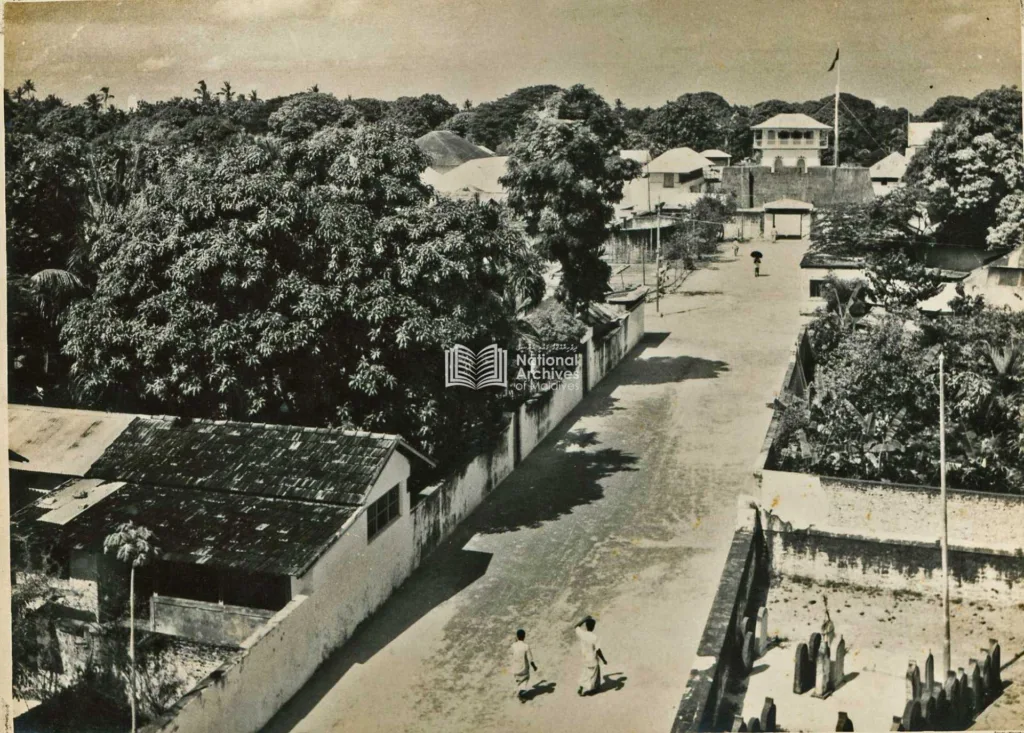

Courtesy of the Maldives National Archives

When the first scientific expeditions reached the Maldives at the dawn of the twentieth century, their interests extended far beyond reefs, currents, and coral lagoons. Alongside charts and soundings, these visitors began to record something far less tangible—but equally enduring: the everyday life of the Maldivian people.

These early encounters marked some of the first systematic attempts to document Maldivian society for a Western audience. Ethnological observations—made with the cooperation of the Sultan—captured aspects of island life that had long existed beyond the gaze of outsiders. Tools of daily use, items of dress, and glimpses of social organization were carefully noted, not as exotic curiosities, but as meaningful expressions of a living culture shaped by the sea.

This shift in perspective was significant. Maldivians were no longer seen merely as inhabitants of a remote geography, but as a people with a distinct identity, social structure, and material tradition worthy of study and preservation. The collections and records assembled during this period reflected a growing recognition that culture, like nature, deserved careful attention.

Crucially, this documentation was made possible through local authority and consent. The Sultan’s support—providing access, representatives, and interpreters—points to a moment of collaboration rather than extraction. It suggests an awareness within Maldivian leadership that the islands were entering a period of increasing global contact, and that recording their way of life held value for the future.

Today, these early ethnological records stand among the earliest Western accounts of Maldivian material culture and social life. They offer rare insights into a society before large-scale modernization—preserving details that might otherwise have faded with time: how communities organized themselves, the tools they relied upon, and the rhythms of daily life in an island nation defined by coral and current.

Viewed from the present, these records carry a dual legacy. They reflect the formative years of anthropology, when scholars began to look beyond landscapes and species to the people who inhabited them. At the same time, they serve as historical snapshots of Maldivian identity—evidence that the culture of the islands was recognized, even then, as unique and worthy of careful documentation.

In an era when cultural preservation has become increasingly urgent, these early efforts remind us that Maldivian society has long been understood as an integral part of the islands’ story. The Maldives have never been just reefs and routes on a map. They are—and have always been—home to a rich and distinctive human culture.