Travelers arriving in Malé often step onto Hulhulé Island with little thought beyond immigration counters, turquoise lagoons, and speedboats waiting to whisk them away. Yet long before Hulhulé became home to Velana International Airport, this small island witnessed one of the most dramatic and controversial events in Maldivian legal history: the first state-recorded hand amputations during the presidency of Mohamed Ameen.

This little-known episode, pieced together from Dhivehi Digest, National Library archives, and the personal accounts of Hakeem Abdulla Yoosuf, offers a rare window into a Maldives shaped by strict legal traditions, political tension, and the human struggle between duty and conscience.

A Call for Help—But No Permission to Act

My own family’s history is intertwined with the event. Two respected Hakeems (traditional heelers) —my grandfather, Hussain Didi, and Addu-born Hussain Manikfaan—were summoned by the government as official medical practitioners. They arrived expecting to provide whatever medical care the law required. But though they stood ready, no instruction came to treat the men after the sentence was carried out. Their role, like many elements of this story, was overshadowed by uncertainty.

The Surprising Witness: Hakeem Abdulla Yoosuf

The central figure became Abdulla Yoosuf from Naifaru in Lhaviyani Atoll. He had not been chosen to perform the procedure, nor had he expected such responsibility. But when the men originally assigned to the task refused out of fear, Shihab urgently called for Abdulla, who happened to be on Hulhulé at the time.

Abdulla would become the first Maldivian in recorded history to carry out a legal amputation.

Nobles Plead for Mercy

The three men sentenced were:

- Hussein Didi of Badi Alibeyge,

- Seedhee (Ibrahim Waheed) of Gomaage, and

- Dhon Mohamed of Omadhoo, Thaa Atoll.

Their crime was theft, but the stolen gold had been recovered and returned to its owners. Because this was the men’s first offense, several nobles—including Bodu Fenvalhuge Seedhee—appealed directly to President Mohamed Ameen.

Under the Shafi’i school of Islamic jurisprudence, they argued, amputation was not required for a first theft. But President Ameen responded firmly:

“I have to execute a sentence ordered by the Honorable Chief Justice.”

Even Ibrahim Faamuladheyri Kilegefaan, a respected statesman whose family name carried great influence, was unable to sway the president.

The stage was set for a historic—and controversial—moment.

Hulhulé Island: A Stage for Justice

Long before runways and airport terminals, Hulhulé was a place known for solemn public events. Decades earlier, it was the site where Hakeem Didi, accused of sorcery, was executed under a coconut palm tree. When crowds gathered once again—this time to witness the amputation of three thieves—it was a reminder of how islands in the Maldives once doubled as courts, prisons, and places of punishment.

President Ameen himself attended. A foreign doctor, though present, was not permitted to conduct the procedure, as he was not Muslim. The responsibility, then, fell to Abdulla.

Fear, Duty, and Improvisation

Sheikh Rushdee advised the soldiers to dislocate the men’s wrists to make the procedure easier. The soldiers tried but could not bring themselves to complete the task. Their hesitation made it clear that, despite the legal order, no one wanted to carry out the punishment.

Abdulla’s question reflected the confusion of the moment:

“What equipment should I use?”

To his surprise, the only items provided were:

- a stove,

- a pan, and

- olive oil.

No proper cutting instrument was supplied. Eventually, someone produced a simple barber’s knife—an improvised tool for a task of enormous severity.

Abdulla, relying on his training, used strips of cloth to restrict blood flow and followed the instructions he had been given. With the crowd watching, he performed the sentences one by one.

A Troubling Aftermath

After completing the procedure, Abdulla returned to Malé uneasy. The men had not received any medical care beyond the basic cauterization done on-site. Leaving them untreated, he believed, was dangerous and irresponsible.

Later that day, he consulted Mohamed Manik of the Maizaandoshuge family, and together they approached President Ameen at Athireege.

“Have they received any treatment?” Abdulla asked.

“No treatment,” Ameen replied. “The law requires amputation and release. They are not arrested after the sentence.”

Nevertheless, he eventually permitted Abdulla and Manik to return to Hulhulé with medicine.

By the time they arrived—about four hours after the amputation—the three men were still lying on the ground, arms wrapped only in cotton. Hussain Manikfaan, who was ill himself, sat beside them in distress.

Later that night, as one of the men, Seedheebe, grew worse, President Ameen called Abdulla again. If necessary, he promised to send the foreign doctor by baitheli, a traditional vessel.

When Abdulla reached the island, Seedheebe was delirious, likely from pain and shock. Abdulla loosened the restrictive bandage and gave him egg yolk to drink, a traditional remedy for strength.

The Voice That Went Unheard: Dr. John Ratnam

What makes this event particularly striking is that a qualified Sri Lankan physician, Dr. John Ratnam, was in Malé at the time. He strongly advised President Ameen not to proceed with the amputations. He even showed the president a photograph of a professional amputation machine and offered to carry out the procedure using anesthesia and tetanus protection.

But his warnings were dismissed.

Historians later wrote that Kuda Ahmed Manik overheard this exchange, and news spread rapidly across Malé. Many were shocked and angered. Even Vice President Velaanaage Ibrahim Didi voiced his disapproval.

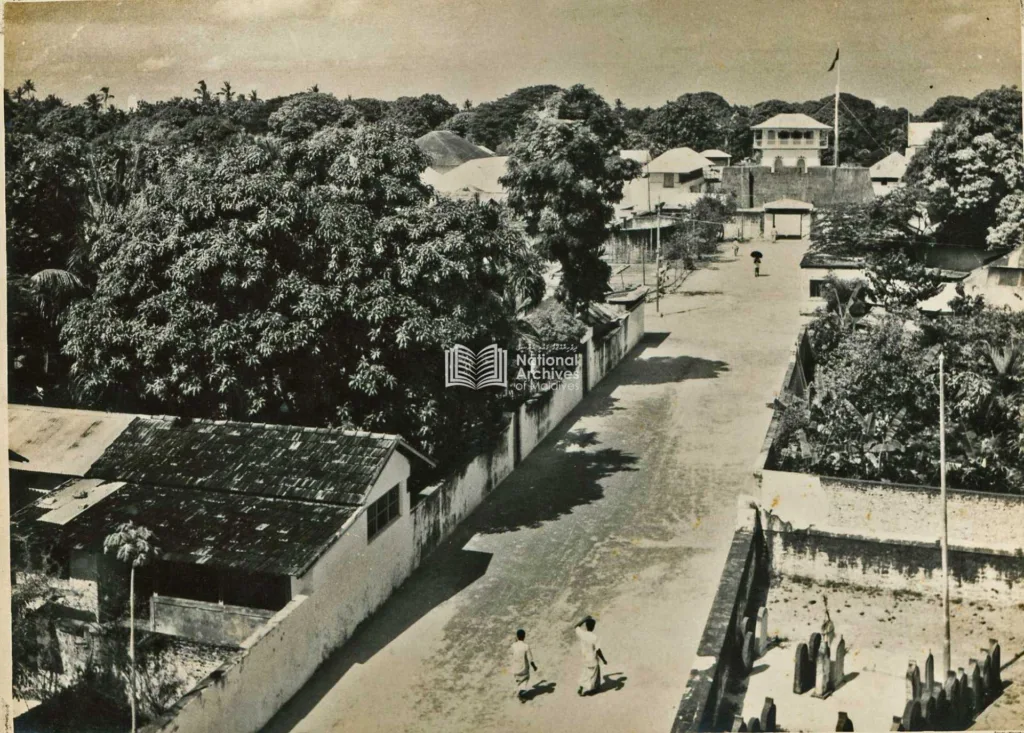

Hulhulé Today: From a Site of Judgment to a Gateway to Paradise

Today, nothing on Hulhulé Island hints at its dramatic past. Travelers step off flights into bright airport halls, greeted by resorts and turquoise water. Few imagine that a short walk from the runway, under what once were coconut palms, a defining moment of Maldivian legal history unfolded.

While the Maldives is best known for its serene beaches and overwater villas, its history is filled with stories that shaped the nation long before tourism began. This episode—grounded in law, culture, religion, and politics—offers travelers a deeper appreciation of how the Maldives evolved, and how justice and authority were once exercised on its islands.

For those interested in Maldivian heritage, the National Museum and the National Library in Malé remain the best places to explore archives and accounts from this period. The story of the Hulhulé amputations stands not only as a historical record, but also as a reminder of how far the nation has come.