By the time a wooden sailing vessel slipped beyond the coral rim of the Maldives, the sea changed character. The water darkened. The horizon widened. And somewhere below, immense and unseen, moved the Bodumas—the “Big Fish.”

To the Maldive Islanders, the ocean was never empty. It was alive, intelligent, and inhabited by forces both benevolent and terrifying. Among the greatest of these beings was the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), a giant that loomed large not as prey, but as presence. Rarely hunted and seldom approached, the sperm whale nonetheless shaped Maldivian culture through fear, folklore, ritual power, and celebration—its influence echoing from sorcerers’ knives to festival streets.

Giants Beyond the Reef

Ethnographer Xavier Romero-Frias records that sperm whales—known in some traditions as favibo—were abundant in the deep ocean waters beyond the Maldivian atolls. These animals did not inhabit lagoons or reefs, but the vast offshore zones where the sea floor falls away and the water turns indigo.

In the Maldivian worldview, whales were not classified as mammals. They were fish—defined not by anatomy, but by where and how they lived. This pre-modern cosmology grouped whales with sharks and other giant sea beings, allowing them to slip easily into myth, ritual, and oral tradition. Biology mattered less than behavior. What lived in the deep belonged to the deep.

The Boat-Eating Big Fish

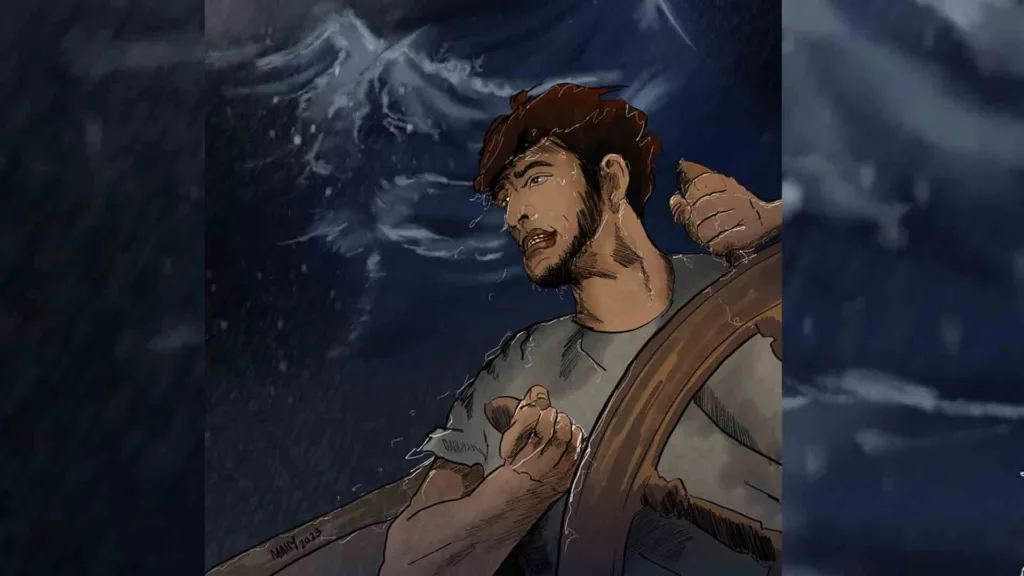

To early Maldivian mariners, the sperm whale inspired awe—and dread. They called it Odi Kaan Bodu Mas, the boat-eating big fish. The name reflected a genuine fear: that such a massive creature could smash or swallow the fragile wooden vessels of the time.

Arab sailors who crossed the same waters shared this anxiety. They referred to whales as Al-baba, and historical accounts describe mariners firing arrows at surfacing whales to drive them away from their ships. Encounters were rare, but when they happened, they left deep impressions—stories retold across generations of sailors navigating the open Indian Ocean.

Oil, Seams, and Survival

Despite the fear they inspired, whales also provided essential materials for survival. While large sperm whales were rarely hunted, smaller whales were occasionally taken. Their bodies were boiled in massive pots to extract whale oil, a resource vital to maritime life.

Before the use of metal nails, Maldivian boats were literally sewn together using coir rope made from coconut husk fiber. Whale oil was used to seal these seams after sewing, acting as both preservative and waterproofing agent. Without it, long-distance sailing would have been impossible.

Whales also produced ambergris, known locally as Maavaharu—a rare, waxy substance sometimes found floating at sea. Highly prized for use in perfumes and traditional medicine, ambergris could bring sudden wealth to those fortunate enough to find it.

Teeth of Power: Sorcery and the Masdayffiohi

The sperm whale’s most enduring cultural role, however, lay not in oil or trade, but in ritual power.

From sperm whale teeth—called masday—Maldivian craftsmen fashioned the handles of sacred knives known as masdayffiohi, or “fish-tooth knives.” These objects were central to faṇḍita, the traditional Maldivian system of sorcery and occult practice.

Because whales were not hunted for their teeth, ivory was obtained only in two ways:

- From dead whales that drifted ashore, discovered decomposing on beaches and regarded as gifts from the sea.

- Through trade with South India and Ceylon when local supplies ran short.

A masdayffiohi was never an ordinary tool. It was a symbol of authority, knowledge, and supernatural command. Every faṇḍita practitioner was expected to own one, and political leaders—such as Atoll Chiefs—were often assumed to possess sorcerous knowledge if they carried such a knife.

Its uses were strictly ritual:

- Immobilizing or commanding evil spirits

- Drawing protective magic circles (ana or aṇu)

- Inscribing magical words on wood or leaves

The knife was never used for cooking or daily tasks, reinforcing the sacred status of sperm whale ivory and the power it embodied.

The Whale Man

In Maldivian folklore, the whale often appears as a liminal being, bridging worlds. Romero-Frias records a striking legend of a man who wandered the oceans for years clinging to the back fin of a giant whale. Over time, the lower half of his body became encrusted with barnacles and seaweed.

Neither fully human nor fully marine, the “whale man” exists between realms—transformed by prolonged contact with the deep. In such stories, the whale is not an animal to be conquered, but an agent of fate, endurance, and transformation.

When the Whale Comes Ashore: Bodu Mas

Today, the legacy of the whale lives on not in fear, but in celebration.

During Eid al-Adha (Bodu Eid), many islands hold the Bodu Mas festival, a massive communal event rooted in ancient sea lore. For days, islanders weave a life-sized whale from coconut palm fronds (fann). Dozens of men then carry the creature through village streets or “swim” it through the lagoon.

The procession is accompanied by Maali Neshun, a performance in which dancers dressed as ghosts and sea spirits—Maali—wear coconut leaves and body paint. Together, the spectacle reenacts an ancient tale of villagers struggling to catch a giant fish, symbolizing unity, cooperation, and the enduring bond between islanders and the sea.

A Living Symbol of the Deep

In Maldivian culture, the sperm whale is not merely an animal. It is fear and fortune, spirit and substance, myth and memory. Respected rather than hunted, classified within a traditional oceanic cosmology, and embedded in ritual, folklore, and festival, the Bodumas remains a powerful emblem of the deep.

Whether imagined as a boat-eating terror, carved into the handle of a sorcerer’s knife, or woven into a giant festival effigy, the sperm whale continues to surface—again and again—in the cultural imagination of the Maldives, carrying with it the mystery and majesty of the open sea.

What Science Sees Today

Modern research now adds a scientific lens to what Maldivians have long known by experience. Contemporary studies offer a clearer picture of the sperm whale’s presence—and absence—in Maldivian waters.

A landmark survey conducted between 1990 and 2002 recorded the following observations:

- Rarity and Range: Sperm whales accounted for just 0.5 percent of all cetacean sightings, appearing almost exclusively along outer atoll slopes and deep offshore waters, far beyond the reefs.

- A Paradox of Absence: Though rarely encountered alive, the sperm whale is the most frequently reported stranded whale species in the Maldives.

- Social Structure: The majority of sightings—82 percent—involved small groups of one to three individuals, most often identified as adult males. On rarer occasions, observers recorded larger schools of 15 to 30 animals, believed to be females accompanied by juveniles.

- Echoes of Loss: Historical records and local memory point to a sharp decline in the mid-20th century. While Yankee whalers targeted the northern Maldives during the 19th century, the most devastating impact came in the mid-1960s, when Soviet whaling fleets killed large numbers of sperm whales in nearby waters. Elder islanders still recall a time when whale blows were a common sight on the horizon—followed by decades of near silence after industrial whaling.