Standing Inside the Stone

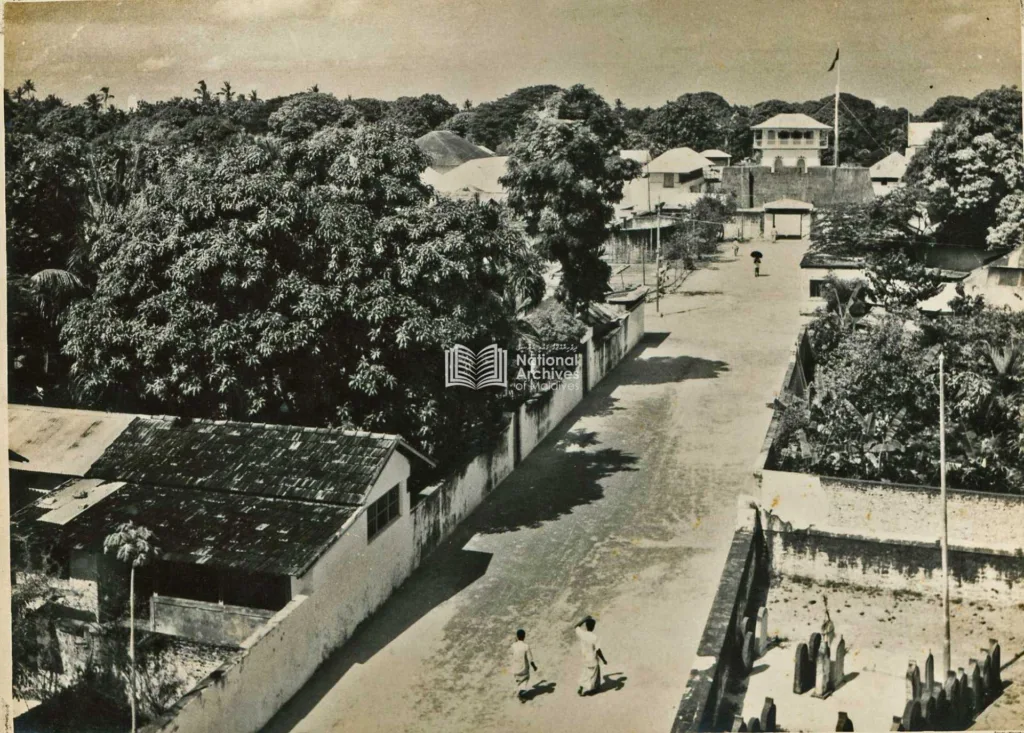

Today, I stood inside Hukuru Miskiiy, in Malé, camera in hand—expecting history, but not quite prepared for awe.

Up close, the coral stone walls revealed themselves as something far beyond masonry. Each block had been precisely cut, its grooves and edges shaped to interlock seamlessly with the next. The carvings were intricate and deliberate, softened by centuries of light and touch, yet astonishingly intact. There was no mortar holding the walls together—only skill, knowledge, and confidence in the material itself.

As I traced the lines of the coral stone, I felt a quiet admiration for the craftsmen who built this place generations ago. These were builders who understood the reef intimately—how it could be cut, joined, and shaped into something enduring. The precision, patience, and artistry embedded in the stone spoke of extraordinary skill, passed down through hands rather than texts.

That moment inside the mosque stayed with me. It prompted questions—not only about how these structures were built, but about what they represented: a meeting of faith, environment, and inherited tradition. To explore those questions, I turned to historical and archaeological research, drawing on several studies and scholarly works that examine the coral-stone architecture of the Maldives and its deep connections to the islands’ religious and cultural past.

What emerged is a story carved from the sea itself.

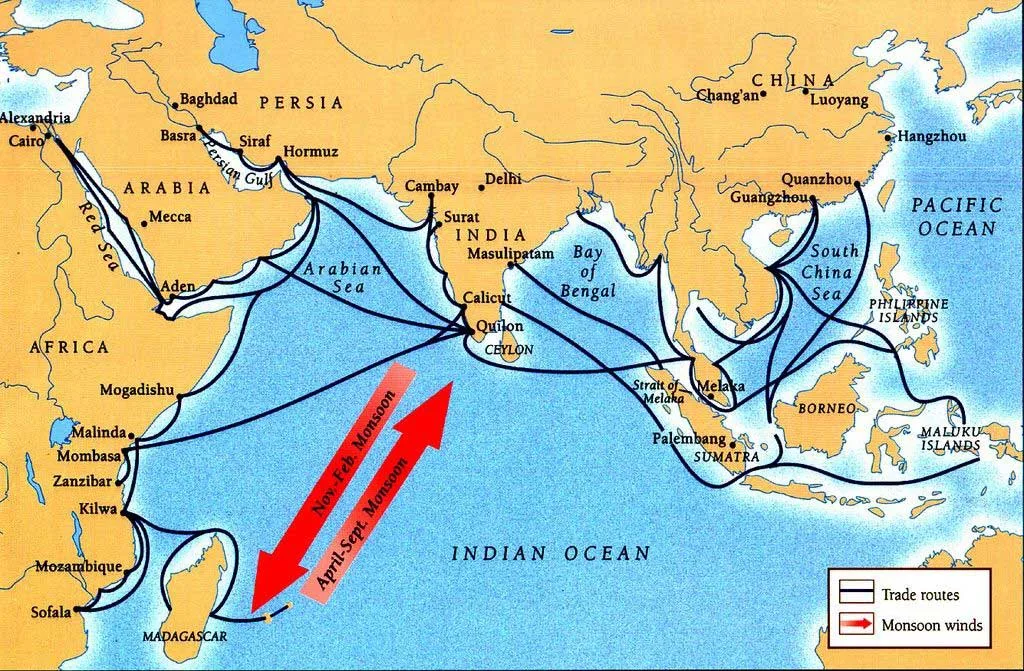

Scattered across the central Indian Ocean, the Maldives is often imagined as a nation shaped solely by sand and sea. Yet beneath its palm-lined streets and modern skylines lies a deeper story—one carved not in manuscripts, but in coral stone. It is a story of transformation, faith, and continuity, preserved in the walls of the country’s oldest mosques.

Across the archipelago, coral-stone mosques rise from islands no more than a few meters above the tide. Built from blocks lifted directly from the surrounding reef, these structures record centuries of belief and craftsmanship—binding religion to landscape in ways found nowhere else in the Islamic world.

Where Belief Changed, but Stone Remained

In 1153 CE, the Maldives embraced Islam, marking a decisive shift in the islands’ cultural and spiritual life. Yet the change did not arrive with imported architectural forms. Instead, early mosques were shaped by what already existed.

Historical and archaeological research shows that finely cut coral blocks—known locally as hiri-ga—were often salvaged from earlier Buddhist monuments. According to architectural historian Mohamed M. Jameel, builders frequently reused stone from stupas and monasteries, sometimes erecting mosques directly atop earlier sacred foundations. Faith changed, but building traditions endured.

This continuity presented practical challenges. Buddhist structures were not aligned toward Mecca, forcing early mosque builders to adapt inherited layouts. As a result, some mosques were constructed at subtle angles, their prayer walls carefully reoriented while older foundations remained intact. The architecture that emerged was shaped as much by devotion as by compromise.

Traces of this layered past remain visible today. Decorative motifs carved into mosque walls echo patterns found in South Asian Buddhist sites, revealing how artistic traditions survived long after religious practices shifted.

Architecture Born from the Reef

By the fourteenth century, Maldivian mosque building had reached a remarkable level of refinement. Writing in the 1340s, the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta described island mosques as elegant and carefully constructed—an observation confirmed centuries later by archaeologists.

These were not masonry buildings bound with mortar. Coral blocks were cut, dressed, and fitted together using interlocking joints so precise that the walls appeared seamless. The technique required intimate knowledge of coral’s grain and fracture lines, allowing structures to withstand humidity, salt air, and monsoon rains.

Inside, coral walls were paired with timber craftsmanship. Lacquered wood panels, carved columns, and intricately assembled ceilings were joined without nails, relying instead on techniques passed down through generations. Scholars identify the period between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries as the classical phase of Maldivian coral-stone mosque construction.

Mosques were not isolated monuments. They stood within sandy courtyards that functioned as cemeteries, where coral tombstones marked the dead—pointed forms for men, rounded ones for women. Nearby, stone-lined ablution tanks recalled older water structures from the islands’ Buddhist past, linking ritual purification across centuries.

Islands of Stone and Prayer

Surviving coral-stone mosques are scattered across the archipelago, each reflecting local adaptations of a shared architectural language. Among the most significant is the Hukuru Miskiiy, or Old Friday Mosque, in Malé, built entirely from coral stone and richly carved with Quranic inscriptions.

Other notable examples stand on islands such as Fuvahmulah, Isdhoo, Fenfushi, and Kudahuvadhoo, where Friday mosques dating from the medieval and early modern periods continue to anchor community life. Though modest in scale, these buildings represent one of the most distinctive mosque traditions in the Indian Ocean world.

A Heritage Under Pressure

Today, the future of the coral mosques is uncertain. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and land reclamation have transformed Malé into one of the world’s most densely populated islands. Historic mosques have been renovated with concrete and modern finishes, often obscuring or replacing original coral fabric.

Some ancient structures have disappeared entirely, dismantled to make room for development. Coral tombstones—once guardians of memory—have been removed or discarded. What remains is fragile, caught between preservation and progress.

Yet the cultural value of these buildings has not gone unnoticed. The Old Friday Mosque in Malé has received international recognition through UNESCO, underscoring the global significance of an architectural tradition born not of imported stone, but of the reef itself.

Stone Sentinels of the Sea

The coral mosques of the Maldives are unlike any others in the Islamic world. They are neither imported nor imitated. They are born of the islands—shaped by tides, belief, and craftsmanship honed over centuries.

Carved from living reef, they remind us that history does not always survive in books or monuments quarried from distant lands. Sometimes, it endures in coral blocks lifted from the sea, fitted together by hand, and left standing to guard the memory of who the islanders were—and who they became.

Sources and Further Reading

Reporting for this article drew on historical, archaeological, and architectural research on the Maldives, including studies by Maldivian architectural historian Mohamed M. Jameel on coral-stone construction; medieval travel accounts by Ibn Battuta and François Pyrard; and early archaeological surveys conducted by H. C. P. Bell. Additional context was informed by documentation and heritage assessments related to the Old Friday Mosque (Hukuru Miskiiy) in Malé, including materials associated with UNESCO recognition, as well as broader scholarship on Buddhist and Islamic sacred landscapes in the Indian Ocean world.

Feature image: Illustration by prominent Maldivian architect Mauruf Jameel, originally shared on his Instagram account (@mai.jameel).