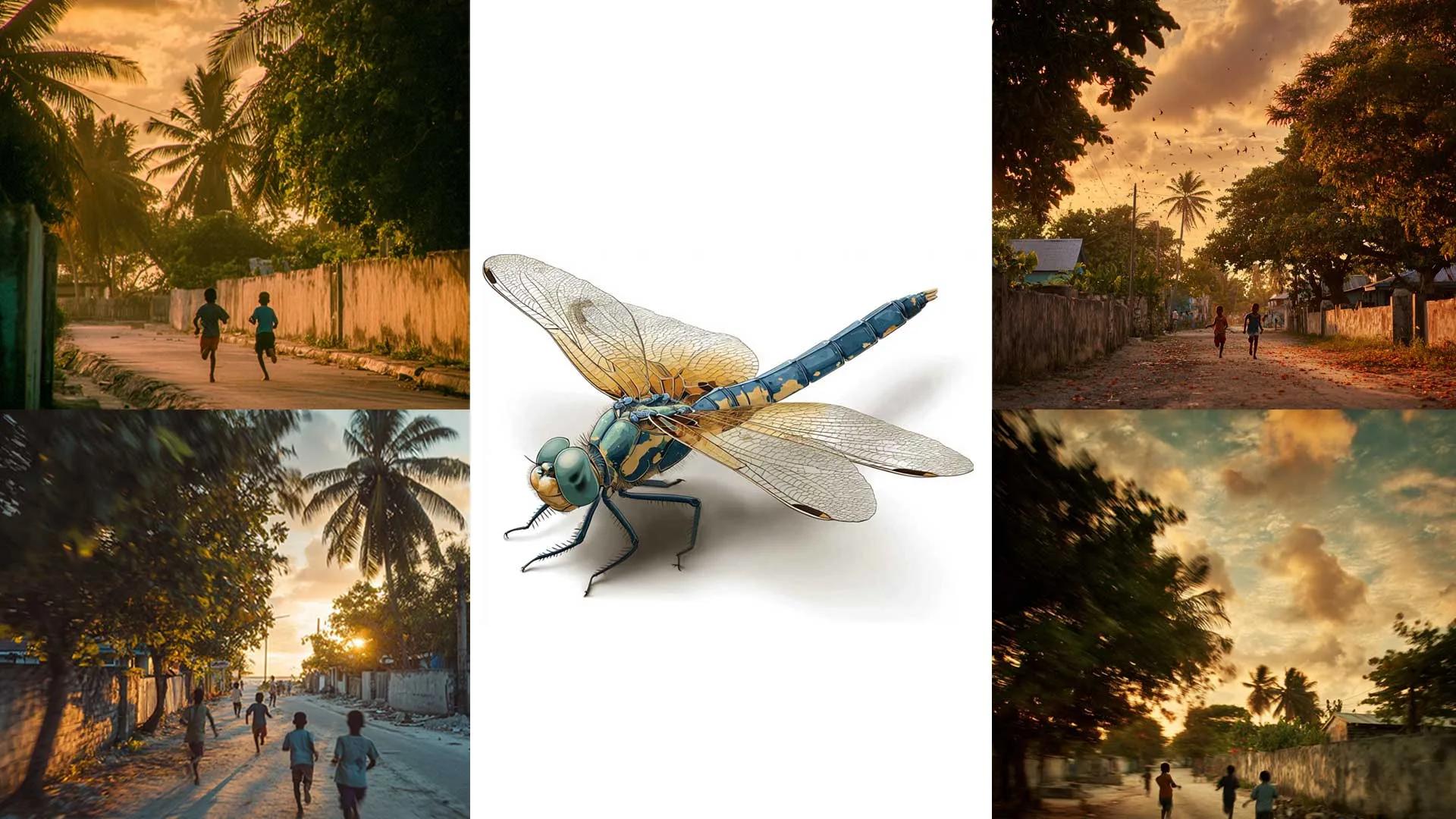

Childhood Adventures on Finimaamagu Road

In the mid-1980s, my friend and I would race along Finimaamagu, the main road in our neighbourhood, chasing dragonflies in the fading afternoon light. We carried ileyshi—a slender stem from a coconut frond—with a delicate banana-fibre string called keylniri tied to its tip. A small dragonfly served as bait for catching the larger, more elusive ones.

Those big dragonflies seemed to fill the entire sky. To reach them, we leapt from one low boundary wall to the next—each only about three feet high but perfect for our childhood pursuits. The frenzy always began between five and half past five, when swarms rose into the warm air, humming above the road and drifting over the rooftops.

We always caught the smaller dragonflies first. Perched on little trees, they were easier to approach. We would lower ourselves into a crouch, taking slow, deliberate steps. When close enough, we stretched out a hand and—if luck favoured us—captured one gently. We tied it to the end of the keylniri and continued our chase, walking, running, and hopping from wall to wall in pursuit of the larger species.

From Childhood Memory to Scientific Curiosity

These memories resurfaced as I prepared a story for the History and Culture section of this website. Wandering recently, I realised how rarely dragonflies appear in large numbers today. Curious, I turned to the internet and soon found two fascinating articles—one by the prolific British writer Daniel Bosley on his blog Two Thousand Isles.

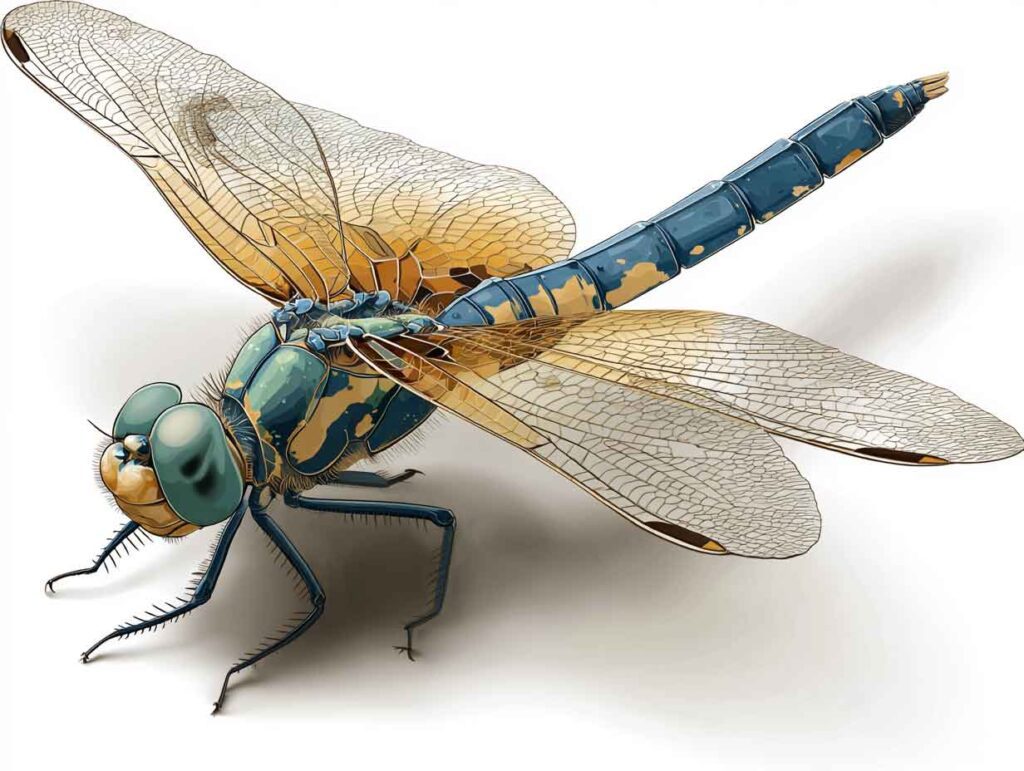

Daniel’s study of dragonflies in the Maldives is exceptional. He identified the Wandering Glider and the Globe Skimmer as the most common species observed in the country, and noted possible sightings of the Pale-Spotted Emperor, Keyhole Glider, and Blue Percher.

His work led me to the research of British biologist Dr. Charles Anderson, who conducted one of the most comprehensive studies on dragonflies in the Maldives. His goal was to understand where these insects originate and how frequently they appear on our islands.

The Epic Migrants of the Monsoon Winds

Dr. Anderson’s findings showed that most dragonflies come from India. One theory suggests they travel at high altitudes, following the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and riding favourable tailwinds. Many migrate from India to East Africa, and on their return in May, some cross the ocean toward the Maldives. The main migration back to India occurs between June and July.

Amazingly, this journey spans four generations of dragonflies and covers roughly 14,000 to 18,000 kilometres, crossing two oceans. While some aspects of this migration remain uncertain, the sheer scale of the journey is awe-inspiring.

And yet a mystery remains: dragonflies cannot complete their life cycle without freshwater—something our islands lack on the surface. Still, every October, millions of them appear across the Maldives, just as they did decades ago when I was a child running along Finimaamagu. Their arrival, timeless and unexplained, remains one of nature’s most captivating phenomena.