Rocky shorelines, shallow reef flats, and deep-sea beds form a mosaic of habitats alive with color and motion. Within these intricate structures thrives one of Earth’s most diverse ecosystems: the coral reef. Though reefs occupy only a fraction of the ocean, they are essential to marine life. Scientists estimate that about 25 percent of all ocean fish species depend on coral reefs at some stage of their lives, finding food, shelter, and safe places to reproduce.

Built by living organisms over centuries, coral reefs are not static formations. They are dynamic systems—constantly growing, eroding, and rebuilding—supporting an extraordinary range of life.

A World of Interdependence

Coral reefs support an estimated 93,000 plant and animal species (Porter and Tougas, 2001). From sponges and sea anemones to sharks and sea turtles, these ecosystems knit together complex food webs in which each species plays a role. Remove one thread, and the balance can unravel.

Reefs also sustain human communities. Millions of people rely on coral reefs for food, income, coastal protection, and even medicine. Acting as natural breakwaters, reefs absorb wave energy, shielding coastlines from storms, erosion, and flooding.

At the core of this living infrastructure are hard corals, which produce the limestone skeletons that form the reef’s foundation. Built grain by grain from calcium carbonate, some reefs grow so large that they are visible from space.

Citizens of the Reef

Thousands of species make coral reefs their home, including:

- Soft and hard corals, fire corals, and sea anemones

- Sponges

- Clams, conchs, sea snails, and cowries

- Fireworms, Christmas tree worms, and fan worms

- Crabs, lobsters, and shrimp

- Sea cucumbers, starfish, basket stars, and sea urchins

- Thousands of fish species

- Sea turtles and sea snakes

These organisms coexist through finely tuned relationships. When one species disappears—often due to overfishing or habitat destruction—the ripple effects can alter the entire reef.

Fragile Foundations

Despite their strength, corals are remarkably sensitive animals. To survive, they require warm, sunlit, clear, salty waters, low nutrient levels, minimal sediment, and a firm surface on which to grow. Even slight changes in temperature or water quality can push corals beyond their limits.

Globally, coral reefs cover about 284,300 square kilometers—less than 0.1 percent of the ocean’s surface and just 1.2 percent of the continental shelf. They are found primarily in three regions:

- The Caribbean and Atlantic

- The Indian Ocean and Red Sea

- The Pacific and Southeast Asia

The Maldives: A Nation Built on Reefs

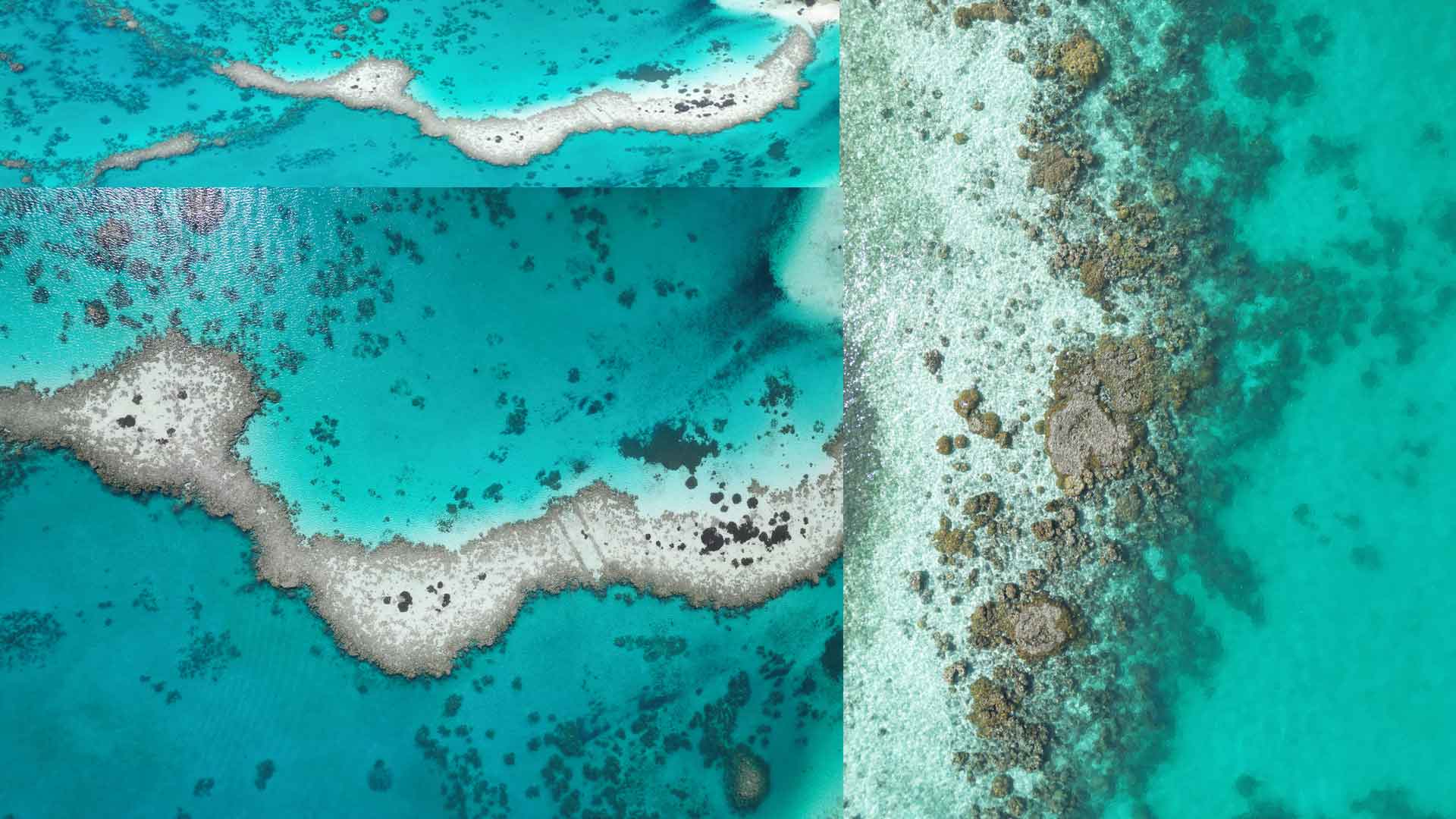

The Maldives is a coral island nation shaped entirely by reefs. Its atolls—ring-shaped reefs encircling lagoons—form one of the most intricate reef systems on Earth. Unique structures known locally as faros add to this complexity, creating lagoons and sandbanks of striking beauty.

Stony corals dominate these ecosystems, forming vast calcium carbonate frameworks. More than 300 reef-building coral species have been recorded in Maldivian waters (Pichon and Benzoni, 2007). The country is widely regarded as a global model for coral reef systems (Naseer and Hatcher, 2004).

The Indian Ocean contains about 11 percent of the world’s coral reefs (Burke et al., 2011). Of that, Maldivian reefs cover roughly 4,500 square kilometers, comprising 2,041 individual reefs—nearly 5 percent of the world’s total reef area and ranking as the seventh-largest reef system globally (Spalding et al., 2001).

Life Beneath the Surface

According to the Maldives Marine Research Institute, nearly 1,000 fish species have been identified in Maldivian waters. Scientists have described 147 species and documented an additional 94, bringing the total to 241. Over 200 coral species spanning more than 60 taxa have been recorded.

The Maldives is also home to five species of sea turtles, 51 echinoderm species, five seagrass species, and 285 species of algae. Many specimens are preserved in national reference collections, offering insight into one of the richest marine ecosystems on the planet.

A Reef Under Pressure

Despite their beauty, coral reefs face mounting threats. Natural disturbances such as storms and disease have always shaped reefs, but human pressures now dominate. Pollution, overfishing, habitat destruction, and climate change are pushing reefs toward collapse.

Between 2014 and 2017, prolonged warm-water events caused coral bleaching across 70 percent of the world’s reefs. The Great Barrier Reef suffered catastrophic losses, and the Maldives was no exception.

In the Maldives, overfishing, land reclamation, coral and sand mining, artificial island construction, and poorly planned coastal infrastructure have accelerated erosion and biodiversity loss (Shareef, 2010). Following the 1998 bleaching event, 60–100 percent coral mortality was documented in some areas (Zahir et al., 2010). More recent studies report 75 percent bleaching, even at depths of 15 meters (Ibrahim et al., 2017; Perry and Morgan, 2017).

A Narrow Window of Hope

Yet hope remains. A 2022 study led by the Coral Reef Alliance, Rutgers University, and the University of Washington suggests that coral reefs can adapt to climate change—if diverse reef systems are protected.

“Corals that have already adapted to warmer conditions can pass that tolerance on,” explains Malin Pinsky of Rutgers University. Protecting reefs in hotter waters, researchers say, may allow resilient corals to seed recovery elsewhere.

“We simply can’t afford to lose coral reefs,” says Helen Fox of the Coral Reef Alliance. “If we do, the consequences won’t just be ecological—they’ll be economic and humanitarian.”

For nations like the Maldives, the future is inseparable from the fate of the reefs. Saving them is not just about preserving beauty beneath the waves. It is about protecting the living foundation of an island world.