Humans have always shown remarkable courage and adaptability, finding ways to survive—and thrive—in every corner of the world. From simple tools to highly specialized techniques, people have learned to master their surroundings with both ingenuity and precision.

In the Maldives, this ingenuity comes to life on the water. The seas surrounding the islands are home to some of the fastest and strongest fish on the planet, and Maldivian fishermen have developed a unique way of pursuing them. This account reveals how skilled local fishermen hunt powerful species like sailfish and wahoo, using a method that relies not on hooks or bait, but on sharp reflexes and time-honed expertise.

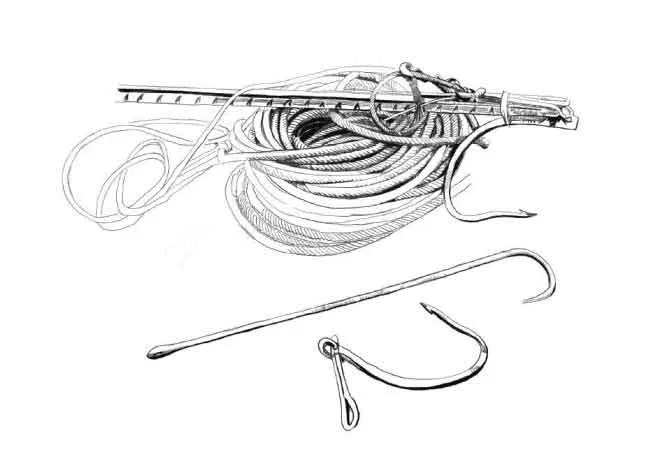

Unlike most fishing practices, this technique does not use live or dead bait on the hook. Instead, fishermen let a piece of wood or a dead fish drift along the surface to draw the predators in—similar in spirit to the traditional harpoon method. Harpooning has long been a classic way to catch large fish in open oceans, and in some parts of the world it was even used in rivers. No matter where it was practiced, the method demanded absolute focus, steady hands, and deep knowledge of the underwater world.

In the Maldives—where the sea is both a livelihood and a legacy—fishing is more than a skill. It is a craft refined across centuries, shaped by moonlight, tides, and the quiet intuition passed between generations of fishermen. Among these traditions, one stands apart: the near-forgotten art of striking some of the ocean’s fastest and most powerful predators with a single, decisive throw.

This method, once common across the islands, was practiced during the full-moon period, when the sea tended to be calmer and visibility improved. Fishermen headed out in daylight during these phases, taking advantage of the clearer water to spot the shapes of large fish below. Their day began before dawn, with the horizon glowing faintly in shades of pearl and violet as they pushed off into the quiet expanse.

In earlier times, these expeditions took place in bokkuras—compact wooden boats—and graceful sailboats that rocked gently with the swell. Only two or three men were needed, though each had to be sharp-eyed, nimble, and completely attuned to the water around them. Armed with a sturdy hook, line, and pole, they relied on a handcrafted wooden decoy carved to mimic the shape of a fish. Cast across the shimmering surface, the lure drifted like a ghostly figure, its shadow gliding beneath the moonlit water and tempting predators from the deep.

Once a predator noticed the lure, it began to stalk with slow, deliberate movements. The fishermen watched every ripple, every faint shift in the current. Timing was everything. Before the creature could bolt, the harpooner needed to deliver a swift, flawless strike. When a fisherman sighted his target, there was a moment—just a heartbeat—when ocean and hunter seemed to hold still together; then, with practiced force, the harpoon arced downward into the glinting body below.

If the throw found its mark, the line snapped free from the pole as the wounded predator surged into the dark blue, dragging the line behind it. The fisherman braced his weight and pulled the line in hand over hand, muscles taut against the resistance of the fish. It was a raw, ancient struggle that bound man and sea in a single, powerful moment.

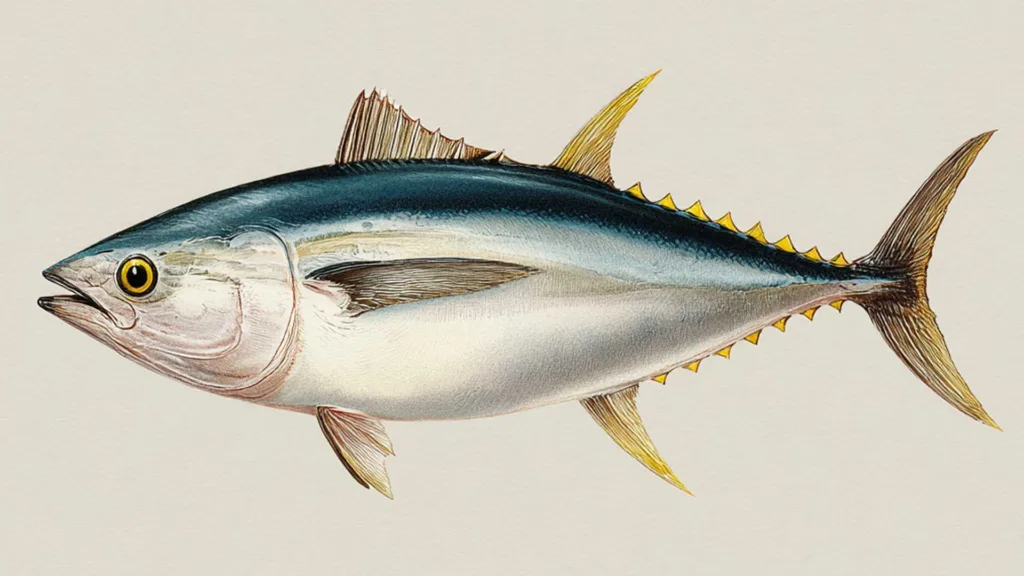

Today, wooden decoys have been replaced by flying fish and mackerel scad, but only a handful of Maldivian fishermen still possess the mastery to perform this remarkable technique. Across the world, harpooning remains a visceral method for capturing giants like bluefin tuna, yellowfin tuna, wahoo, and swordfish. In the Maldives, however, modern practices now dominate. Trolling, jigging, and popping are the preferred ways to pursue the swift and elusive wahoo, though slow trolling with live baits such as mackerel scads still stands as a cherished tradition.

Long before modern gear, Maldivian fishermen showed remarkable ingenuity, landing lightning-fast fish using nothing more than the spathe of a banana plant. These stories, passed down like treasured heirlooms, speak of a time when survival depended on skill, patience, and an intimate understanding of the sea.

What remains of this art is more than a method of fishing—it is a glimpse into the heart of Maldivian heritage. In these islands, where the ocean is both provider and teacher, traditions like these remind us of the beauty and resourcefulness woven into the history of life at sea.