Drawing on Xavier Romero-Frias, “4.1.1 Tutelary Spirits,” in The Maldive Islanders, and Hasan Ahmed Manik’s Maldivian Myths

When elderly people — and even others who claim to have seen spirits or strange creatures — tell their stories, we listen with a sense of fear in our minds. Different kinds of tales begin to fill and confuse our thoughts, putting us in a state of uneasiness: fear of the dark, fear of trees, beaches, certain places, and so on.This article is about a well-known spirit in Maldivian folklore, one that many people have shared stories about.

In the Maldives—an archipelago of shimmering lagoons, quiet reefs and a long memory carried by the ocean breeze—few supernatural figures intrigue the imagination quite like Baḍi Fereytha. Known by a dizzying constellation of names, this spirit is said to answer to Baḍi Edurukalēfānu, Badi-Edhurukaleyge, Badirasrahaa, Kaleyfaanu, Maabei, Kuda Kujjaa, Kirufeli-Huni Hussain Kaleyge, Badifureytha, Hudhu Meehaa, Babarey, Kahafureythayaa, Maabeya, Bodu Baburu, and more.

These names shift depending on the island, the storyteller, and the cultural memory of each community. Their sheer number signals not confusion, but the dynamic nature of folklore: the spirit known today as Baḍi Fereytha is a composite entity, a guardian-spirit shaped over centuries as beliefs evolved, merged, and sometimes clashed.

A Spirit Born in Modern Times

Despite the spirit’s present-day notoriety, there is no mention of Baḍi Fereytha in the ancient strata of Maldivian mythology. This absence, as Xavier Romero-Frias explains in his analysis of tutelary spirits, is significant. Even Ahmad Haji Edurukalēfānu, an 18th-century scholar known for his exhaustive satirical poem listing local spirits, does not include Baḍi Fereytha among the supernatural beings of his time.

The absence has a logical explanation. The Divehi word baḍi means gun, and guns were not introduced to the islands until relatively late in their history. A spirit wielding a gun—and described as wearing an 18th-century military uniform—could not plausibly belong to the pre-Islamic era of goddesses, ocean spirits, and ancient demons. His supposed fluency in Arabic, spoken and written, further anchors him in a period when Maldives was increasingly exposed to Arabian scholarship and religious authority.

Within this context, Baḍi Fereytha appears to be a post-Islamic reinterpretation of older spirit archetypes, emerging during a time of intense cultural transformation. As religious elites sought to harmonize Maldivian beliefs with Arabian orthodoxy, many older spirits were demonized, reclassified, or reshaped. Baḍi Fereytha carries the unmistakable marks of that era—a guardian spirit built from fragments of older myths but remodeled in the image of modern influence.

Ancient Echoes Behind the Gun

Yet Baḍi Fereytha is far from rootless. Romero-Frias traces his deeper ancestry to earlier male guardian figures who once populated Maldivian oral tradition. These include shadowy warriors who were said to emerge from the sea carrying swords, as well as protectors linked to the fearsome haybōrāhi, the seven-headed serpent that dominates several early myths.

Beyond the Maldives, parallels stretch across the Indian subcontinent. Dravidian tutelary deities such as Murugan, with his deadly spear, or the village guardians Māḍan and Ayyanār, all bear weapons and serve as fierce protectors of the community. Their imagery—mustached, armed, vigilant—echoes faintly in the figure of Baḍi Fereytha, suggesting that the spirit may be an island variation of a broader South Asian archetype.

Romero-Frias highlights another unexpected layer: some later Maldivian poems attribute Baḍi Fereytha’s parentage to the celestial couple once associated with Oḍitān Kalēge, the legendary sorcerer-sage of ancient Divehi lore. The shared ancestry appears too precise to be accidental. Instead, it reflects a deliberate blurring by reformist scholars seeking to undermine the revered pre-Islamic hero by entangling him in monstrous narratives. Here, Baḍi Fereytha becomes a symbolic vessel for cultural conflict, his identity shaped by competing versions of the past.

Hasan Ahmed Manik’s Baḍi Fereytha: A Frightening DĦEVI

While Romero-Frias offers historical depth, Hasan Ahmed Manik brings Baḍi Fereytha into the vivid light of living folklore. In Maldivian Myths, he describes this spirit—under its numerous names—as a powerful and dangerous DĦEVI, “an infidel of the worst type,” feared across islands.

According to Manik, the spirit:

- always carries a gun, reinforcing its modern origins,

- appears if its name is spoken three times,

- haunts the world on moonlit nights or after a gentle drizzle,

- and reveals its presence through the drifting scent of screw-pine flowers.

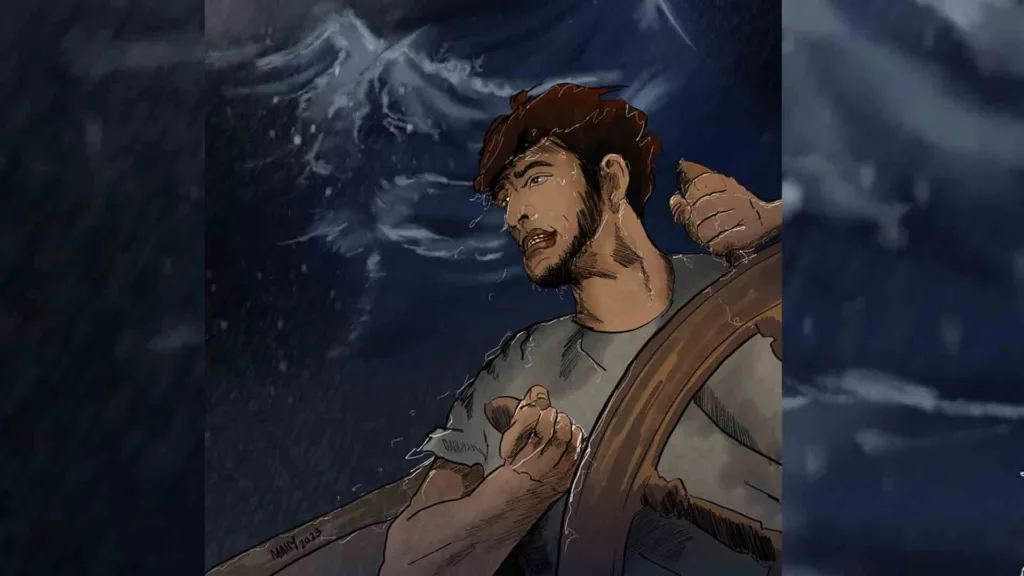

These sensory markers—light, scent, sudden appearance—are central to islander testimonies. On isolated footpaths or jungle lanes, villagers describe seeing small, short humanlike figures emerging from the darkness. These beings move toward the nearest source of light before vanishing abruptly, leaving only silence in their wake.

Many witnesses claim the spirit is completely black, its features impossible to discern. Some insist that different names—Kuda Kujjaa, Hudhu Meehaa, Maabei—refer to forms of the same entity, appearing in different locations or contexts. The spirit’s behavior, too, varies: sometimes it crosses roads, sometimes it appears near homes or office buildings, always briefly and without explanation.

A Living Patchwork of Belief

Taken together, the accounts of Romero-Frias and Manik reveal a compelling portrait of a spirit with a foot in two worlds. Baḍi Fereytha is at once ancient and modern, local and foreign, mythic and alive. His many names, weapons, origins, and behaviors show how Maldivian folklore adapts to cultural upheaval, blending fragments of Dravidian mythology, island memories, and the pressures of Islamic reform.

From Romero-Frias, we understand Baḍi Fereytha as an evolving guardian spirit shaped by historical tides. From Manik, we encounter the spirit not as metaphor, but as a presence woven into the nightly rhythms of island life. Together, they show that this DĦEVI—whatever name he takes—remains one of the Maldives’ most potent and unpredictable supernatural beings, an enduring reminder that in the Maldives, the past never fully disappears.