In the intricate social world of the ancient Maldivian coral atolls, few figures commanded as much respect—or inspired as much quiet awe—as the keyolhu, the master fisherman. While kings ruled from the capital of Malé, it was the keyolhu who governed the vast and unpredictable ocean surrounding each island. Drawing on ethnographic accounts recorded in The Maldive Islanders by Xavier Romero-Frias, Maldivian oral tradition portrays the keyolhu not merely as an expert mariner, but as a guardian of life, sustenance, and secret knowledge at the edge of the known world.

To the fishing communities of the atolls, the sea was not an empty expanse but a living domain—sometimes generous, sometimes hostile—inhabited by unseen forces. The keyolhu stood at the boundary between human society and this “Blue Kingdom,” exercising authority that was at once practical, ritual, and moral.

Authority on the Open Sea

In many islands—especially in the southern atolls—the status of the keyolhu was exceptionally high. Fishermen obeyed him with unquestioned loyalty, for their survival depended on his judgment. A successful expedition could sustain an entire island; a failed one could bring hunger and hardship. I asked linguist Fathuhullah Salih about the legendary term keyolhu. He explained that across the Maldives, keyolhu commonly refers to the chief fisherman, though in some regions the role is also known as maakeyolhu or keyolhube.

In earlier times, senior fishermen—particularly the keyolhu—carried a madiseela, a small box containing betel leaf, areca nut, and other personal or ritual items. This box was often hung from the kumbu kafi, a symbolic place within the vessel, underscoring the fisherman’s authority and ritual standing. In some communities, fishermen would even bring a portion of their catch to the keyolhu’s house, acknowledging his leadership not only at sea but within the social fabric of island life.

Hussainbe, a fisherman from Dhadimagu Ward in Fuvahmulah, described the deep respect accorded to the keyolhu. He explained that fishermen would never touch or take the huvanifeyshi, a special box carried by the keyolhu and hung from the kumbu kafi. The box, he said, contained special hooks, betel leaf, areca nut, and often a thaveedhu (amulet). “The crew respected him completely,” Hussainbe recalled. “They never touched the huvanifeyshi. They obeyed the keyolhu and showed him respect both at sea and in everyday island life.”

This authority was visible across all types of fishing vessels—from small wooden bokkura to large dhoni. Island fishermen emphasized that a keyolhu was not defined by physical strength, but by experience and mastery. He understood the sea, the weather, and countless subtle factors essential to fishing. A keyolhu was also a master of knots, hooks, and lines, and an expert in landing powerful fish. One might sail with a keyolhu who appeared neither muscular nor imposing, yet when it came time to bring in massive yellowfin tuna or sailfish, his skill became unmistakable. Fishermen recalled keyolhu who would dive into the sea without masks to assess the movement of large pelagic fish—sailfish, black marlin, yellowfin tuna, and even sharks. This quiet command of knowledge and technique is why they were called keyolhu: master fishermen and chiefs of the sea.

The Architect of the Deep

The position of keyolhu was not attained by chance. It was earned through decades of experience and mastery of a highly specialized body of knowledge. A true master fisherman could “read” the ocean—detecting subtle changes in water color, recognizing the flight patterns of seabirds, sensing shifts in wind, and interpreting the movement of currents.

This knowledge extended to the timing of the nakaiy, the traditional stellar calendar used to determine the most auspicious moments for fishing. The keyolhu also oversaw the construction and preparation of the dhoni, organized the crew, and directed the distribution of the catch. His authority on board was absolute, tempered by responsibility: the safety of both crew and island rested in his hands.

Ritual, Spirits, and the Sea

The dhufaa foshi is a staple of Maldivian maritime life, serving as a portable pantry for the ingredients used in the dhufun ritual. Whether a simple cloth madiseela or an intricately carved box, it holds the stimulants and spices that sustain fishermen through long hours beneath the equatorial sun. For the keyolhu, this takes a more specialized form: a box known as the huvani feyshi, used to store special hooks and ritual items. Hidden within the box is a secret drawer containing objects such as the thaveedhu (amulet), underscoring the blend of skill, belief, and secrecy embedded in the practice of fishing.

Beyond technical skill, the keyolhu was believed to possess ritual power. Fishing success was often attributed not only to experience but to faṇḍitha—esoteric knowledge combining incantations, taboos, and protective rites. It was widely believed that certain masters could attract tuna shoals, repel misfortune, or shield their boats from malevolent spirits.

One enduring legend speaks of a keyolhu from Alifuṣi whose abilities were whispered to be supernatural. Before beginning a fishing expedition, he would leap into the sea at the prow and swim beneath the length of the vessel, emerging at the stern to recite secret formulas. This ritual act was believed to “seal” the boat, protecting it from spiritual interference and ensuring an abundant harvest. Such stories, passed down through generations, reflect how deeply fishing was woven into both belief and identity.

Secret Knowledge and Inheritance

The knowledge of the keyolhu formed a closed system, transmitted orally and often kept within families or tightly knit circles of practitioners. Fathers instructed sons; masters trained chosen apprentices. This “secret science” included not only navigation and seasonal knowledge, but also competitive rituals—such as vahuthaan—believed to influence fish movements or counter the magic of rival crews.

Because this knowledge was never written down, the death of a great keyolhu was mourned as more than a personal loss. It marked the disappearance of an entire archive of lived wisdom, accumulated through years of observation, ritual practice, and intimate engagement with the sea.

A Vanishing Lineage

With the arrival of modern technologies—outboard engines, sonar, and GPS navigation—the traditional role of the keyolhu has inevitably changed. Intuition has been supplemented by instruments; ritual has yielded ground to efficiency. Yet the cultural memory of the keyolhu endures.

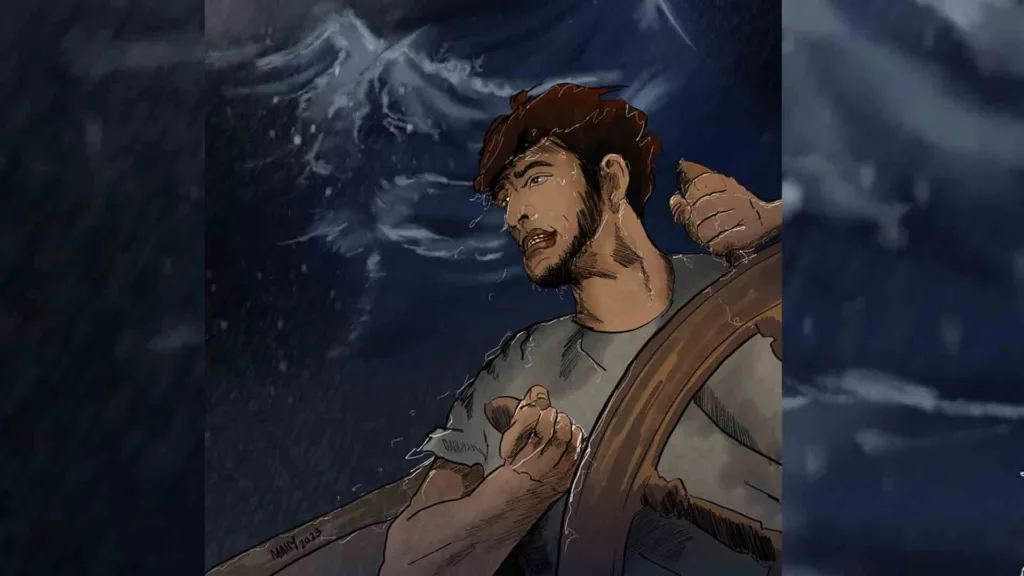

They are remembered as iron-willed navigators who stood at the prow of the dhoni, reading wind and water with nothing more than experience, discipline, and belief. In the collective imagination of the Maldives, the keyolhu remains a symbol of harmony between human skill and the living sea—a reminder of a time when survival depended not only on strength and labor, but on knowledge whispered from master to apprentice, and from ocean to man.