In the quiet stillness of the night, silence was often broken by frantic knocking on our simple wooden door. A familiar voice would call through the darkness: “Saliheybey!”

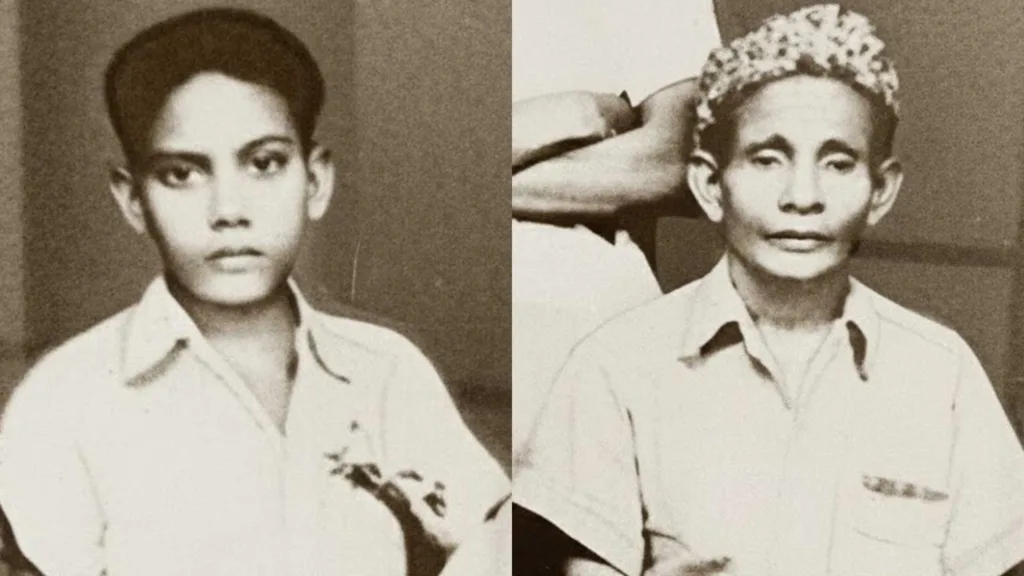

In those moments, my father—one of the island’s few community health workers and a skilled traditional medical practitioner—rose instantly. In our island community, our home became a beacon for anyone facing a medical emergency. People arrived desperate and pleading: a loved one who appeared lifeless from sickness, someone unconscious, or a mother enduring painful labor.

I can still picture those midnight visitors with startling clarity. On one unforgettable night, a man arrived breathless, pounding on the door in a frantic rhythm. When my father opened it, the man gasped, “A cockroach has crawled deep into my wife’s left ear!” Without hesitation, my father grabbed his signature bag—a simple kit of scissors, forceps, and essential medicines that he carried everywhere.

Healers of the Night

Whether the emergency was a fracture, a deep wound, or a difficult birth, my father mounted his bicycle and pedaled off—no matter how dark the night or how fierce the storm. Through the narrow, winding roads of Fuvahmulah, he reached every corner of the island, answering each call with calm assurance and unwavering care.

At a time when there were no hospitals, ambulances, or diagnostic equipment on the island, healers like my father were the frontline of community healthcare. Trust in them was absolute. Their skills were shaped by experience, necessity, and compassion rather than certificates or machines.

Daytime Emergencies and Island Traditions

The work did not end with sunrise. I remember a young girl who was brought to us during the day with a gruesome injury. She had been using a kathivaalhi, a traditional Maldivian knife, to crack open an Indian almond nut when the blade struck her index finger.

Her parents waited a full day before seeking help. By the time they reached my father, the wound had deteriorated badly. The tip of her finger had become necrotic—its tissue beyond saving. With steady hands, my father performed a surgical amputation, removing about an inch and a half of decayed tissue (part of the finger) from the tip of the finger. After applying a numbing spray, he used a simple, sharp surgical tool to cut away the affected area. The spray eased the pain but could not fully numb it. He then carefully cleaned the wound and applied a fresh dressing.

Daytime also brought moments deeply rooted in island culture. One of the most social and memorable aspects of my father’s work was circumcision, known locally as hithaanu kurun. In the early morning hours, my father and his close friend, Hussainbeybey, would visit homes where young boys were prepared for this important rite of passage.

I accompanied them on several occasions in the mid-1980s. As my father prepared his razor-sharp barber’s knife, I lost my courage—turning my head away and squeezing my eyes shut. While my father worked, Hussainbeybey prepared the dressings, using cotton soaked in benzoin. Often, five or six boys would be circumcised in one session.

When it was over, anxiety gave way to relief and celebration. Morning tea was shared, and tables filled with Maldivian short eats and traditional delicacies prepared by grateful families.

The Healing Wisdom of My Grandfather

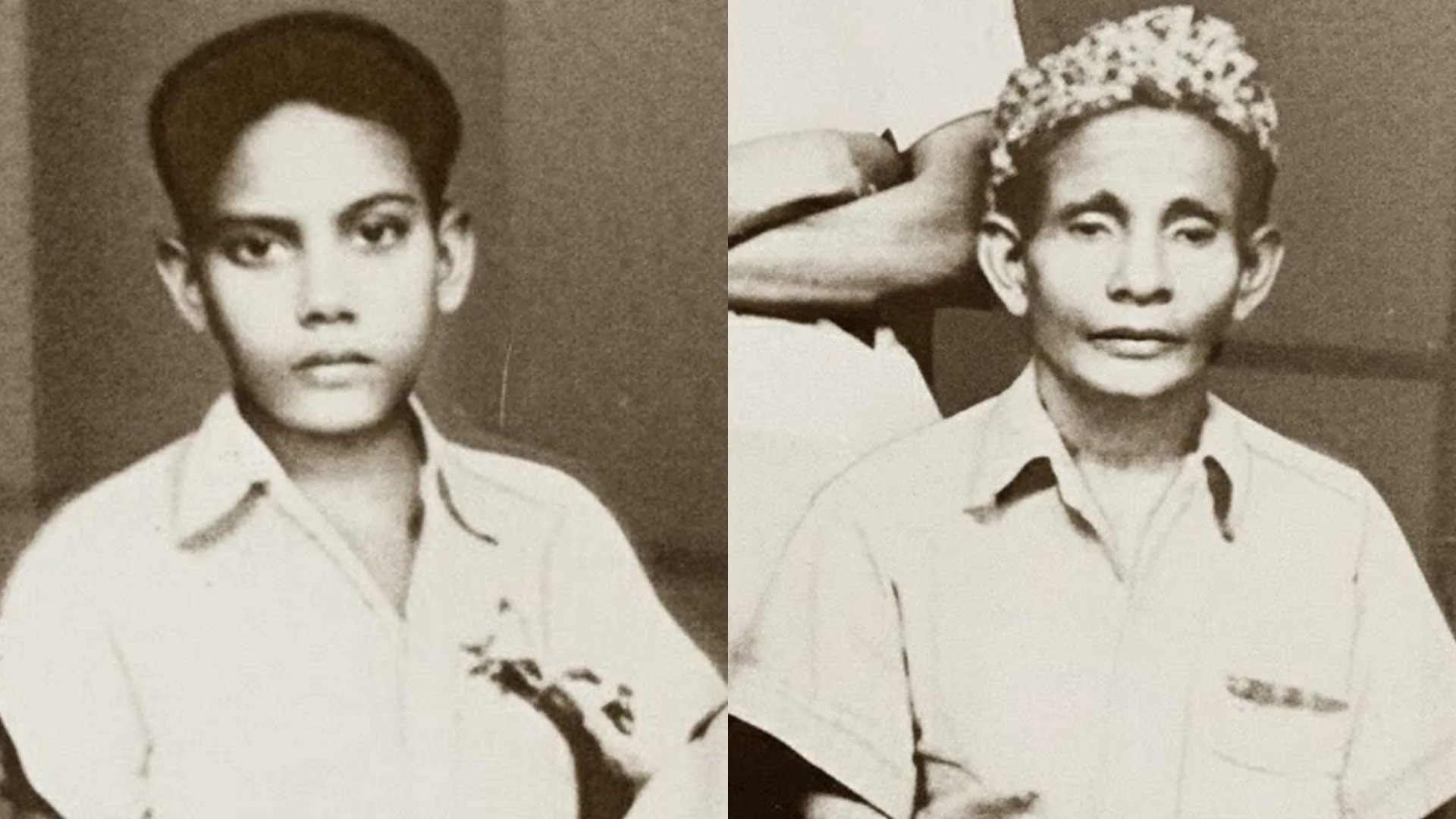

The knowledge my father carried did not begin with him. It was inherited from my grandfather, Hussain Didi (Kudubae), a respected traditional healer whose understanding of herbs, oils, and remedies shaped generations.

This form of healing is often referred to as Unani medicine. My grandfather learned through experience and from other Hakeems—traditional medical practitioners and healers—of his time. Later, my father learned from him, continuing the practice and producing a wide range of medicines that served Maldivian communities for more than half a century.

Stories of my grandfather’s work were shared with me by my father; my late uncle, Abdulla Rafeeq; my father’s cousins, Dhonbea and Hassanbea; and elderly people who had witnessed my grandfather’s practice. They recalled how people would rush to our dheyliya (home) for emergencies—men falling from tall coconut palm trees, deep cuts from furey (large wood-cutting knives), high fevers, swollen limbs, bee attacks, and more.

When patients could not move, my grandfather would walk long distances along island roads to attend to them, no matter how far away they lived.

Fractures, Travel, and Service Beyond the Island

My grandfather relied on medicinal plants available in Fuvahmulah, along with essential ingredients he obtained from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) during his travels aboard his own Vedi (sailing vessel). He kept sarubaths (medicinal syrups), oils, and prepared remedies ready at home for emergencies, while other treatments were mixed fresh according to the injury or illness.

One of the most valued treatments of the time was ruigalu beys, used for fractures and muscle sprains. A thick paste made from habaro was applied to broken limbs, after which bamboo sticks—about ten inches long and one inch wide—were secured around the injury. As the paste dried, it hardened into a rigid casing, functioning much like a plaster cast.

My grandfather’s reputation extended beyond Fuvahmulah. He traveled to other atolls to treat patients and was occasionally summoned by the central government to assist with serious medical emergencies. Along with other specialist Hakeems, he was called to Malé to attend the first recorded hand amputation in Maldivian history during the presidency of Mohamed Ameen.

He was widely regarded as one of the most respected healers of his era.

A Living Legacy

That legacy continued through my father—not only in knowledge, but in ingenuity. He hand-crafted delicate copper instruments designed to remove foreign objects from ears and noses, tools that proved invaluable time and again.

About fourteen years ago, a young boy was rushed to Fuvahmulah Hospital with a lithium battery stuck in his nose. Doctors were unable to remove it and planned to refer the child to Addu Atoll Hospital. When the boy’s father learned my father was nearby, he sought him out. Using his small copper tool, my father gently removed the battery within a minute.

From easing pain to assisting in birth, from night-time emergencies to cultural rites, my father and grandfather—and others like them—formed the heartbeat of island healthcare. In a time before modern medicine reached every shore, they stood as trusted healers, guided by tradition, skill, and deep compassion.

Their story is not just one of medicine, but of island life itself—of resilience, responsibility, and service to community.