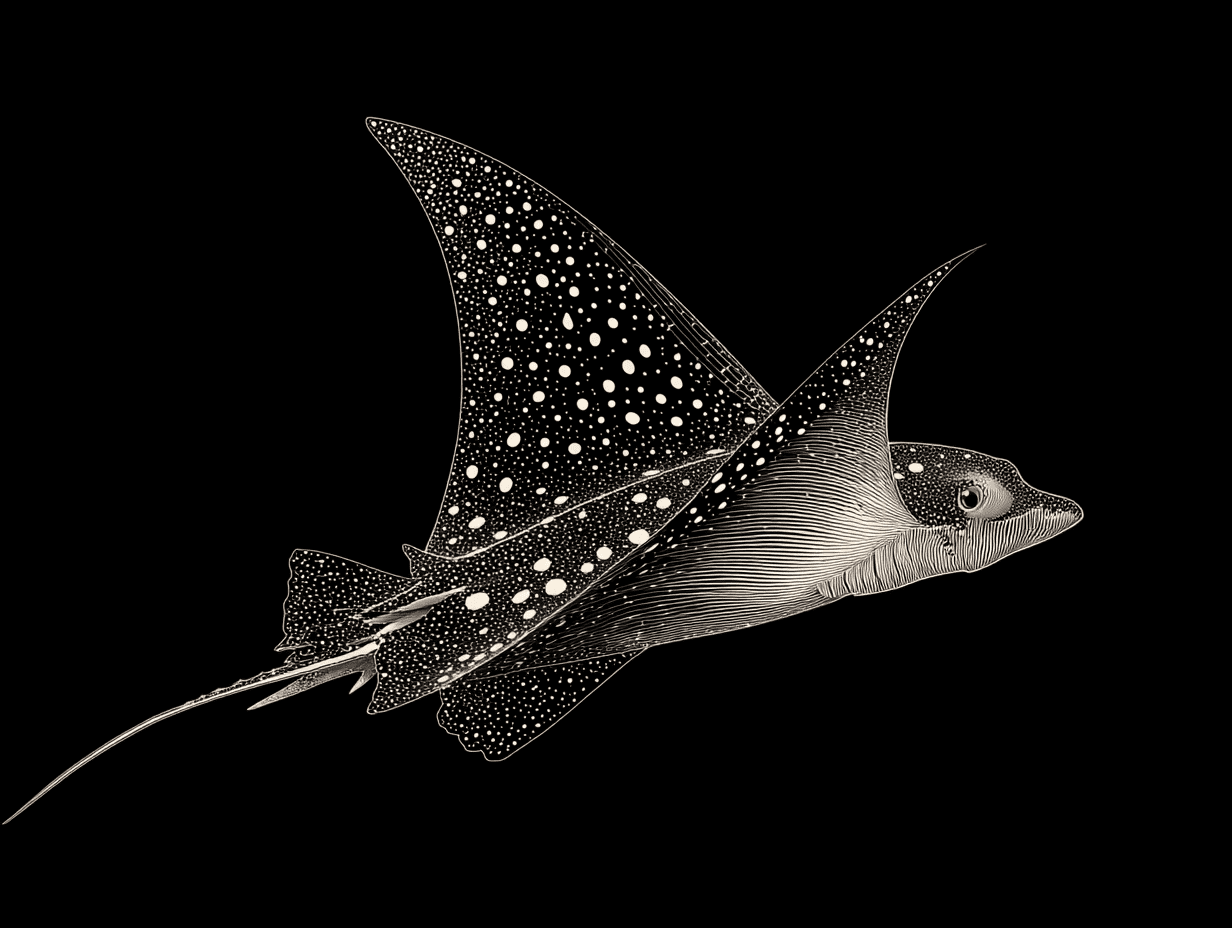

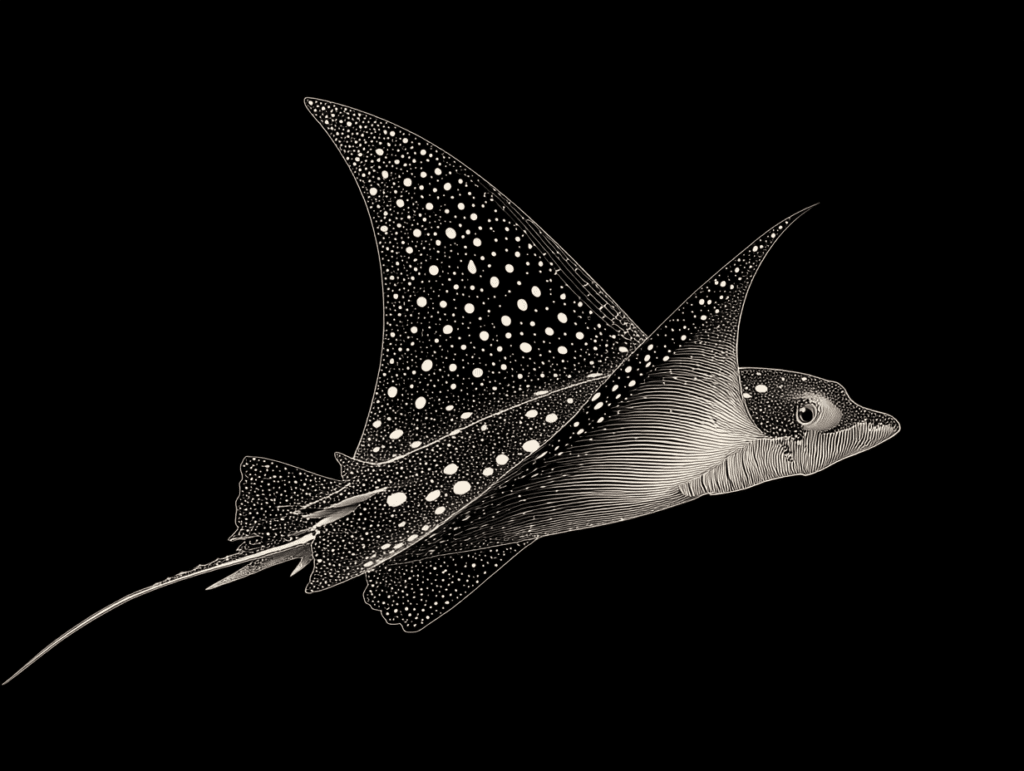

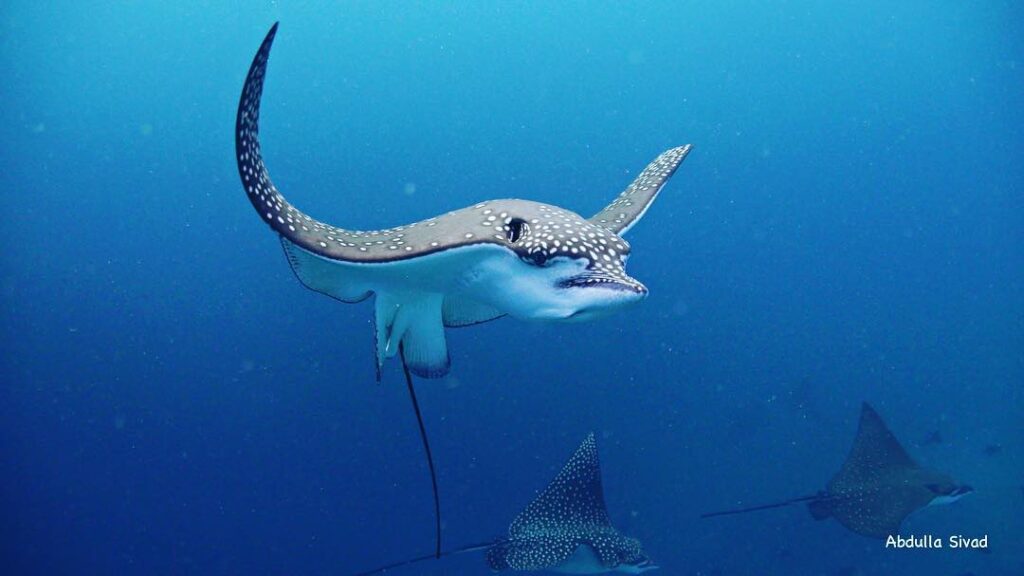

The white spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari) is locally known as vaifiya madi. This graceful, swift swimmer often forms enormous schools near the surface or much above the bottom, and it is sometimes observed leaping far into the air. In the afternoon, it likes open water and goes to the bottom to feed, mostly on big sand flats that are between the beach and reefs.

To protect its disc, it has a small dorsal fin near the base of a very long, whip-like tail that is 2.5 to 3.0 times the width of the disc when it is not hurt. Just behind the dorsal fin, there are one or more poisonous spines. This species has a maximum width of 3 metres. And its tail can grow to five meters long.

The duck-like nose digs into the sand to find food, which it then breaks up with its strong, plate-shaped teeth. Eagle rays eat clams, whelks, oysters, and crabs.

There are white spots on eagle rays that live in shallow water near coral reefs and bays. Most of the time, they live about 80 meters below the surface. They seem to be in schools. But they spend most of their time out in the open water.

The true spotted eagle ray (A. narinari) lives in the Atlantic, the ocellated eagle ray (A. ocellatus) inhabits the Indo-Pacific, and the Pacific white-spotted eagle ray (A. laticeps) resides in the East Pacific, as they have recently been split into three groups.

The tides influence their movement. They are also more active at high tide. Usually, we find them in large groups or schools, but we have also seen them alone in shallow water.

In the Maldives, we are fortunate enough to encounter groups of roughly 20 of them.

Researchers from the Harbour Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University conducted a study in 2020 to learn more about the behaviour, movement, and habitat utilisation of white-spotted eagle rays.

Researchers used acoustic telemetry and transmitters with unique codes. The study found that they use it during the day and at night when the water is shallower. In the ocean and lagoons, they move faster. For the most part, they move slowly in these places.

The research indicates that eagle rays may spend a greater amount of time in the lagoon’s shallow water in search of food at night than they do during the day.

Understanding the use of channels is crucial for evaluating risks and potentially devising strategies to safeguard the white-spotted eagle ray from adverse effects.

According to Breanna DeGroot, M.S., lead author, research technician, and former graduate student working with Matt Ajemian, Ph.D., co-author and assistant research professor at FAU’s Harbour Branch, “Both channel and inlet habitats receive a lot of human activity, such as boating and fishing, and are vulnerable to coastal development impacts from dredging.”

Moreover, cooler and darker conditions caused rays to move to deeper depths, whereas warmer and lighter conditions caused them to spend more time in the channels and inlets. The temperature significantly increased the rate of movement, indicating that warmer temperatures are more conducive to ray activity.