For more than a thousand years, life in the Maldives has depended on the ocean—not as a boundary, but as a bridge. Long before modern harbors, engines, and navigational instruments, islanders built vessels capable of crossing vast stretches of the Indian Ocean using little more than wind, stars, and inherited knowledge. Among these vessels, none was more vital to survival than the vedi, a sailing ship engineered not for comfort or speed, but for endurance.

Long before overwater villas and seaplanes defined the Maldivian horizon, the survival of the archipelago rested upon a masterpiece of traditional engineering: the veḍi. While Maldivian folklore is filled with tales of the sea’s dangers, the veḍi was the physical answer to those threats—a vessel built not merely for travel, but for the endurance of a nation.

The Architecture of the Horizon: Stitched Hulls and Coir

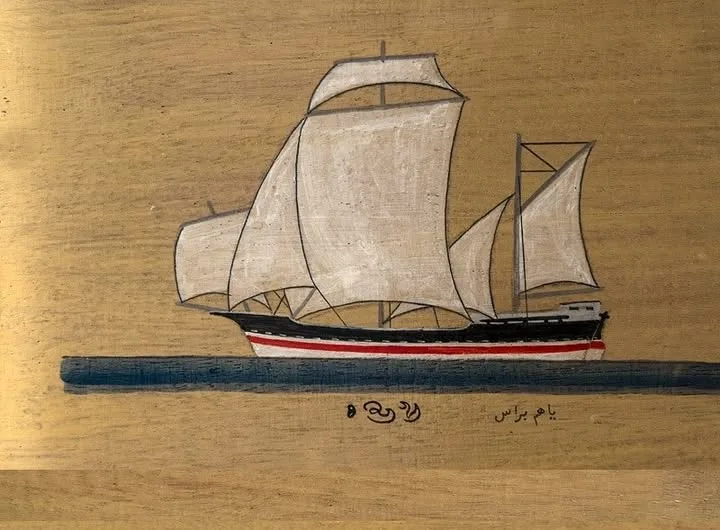

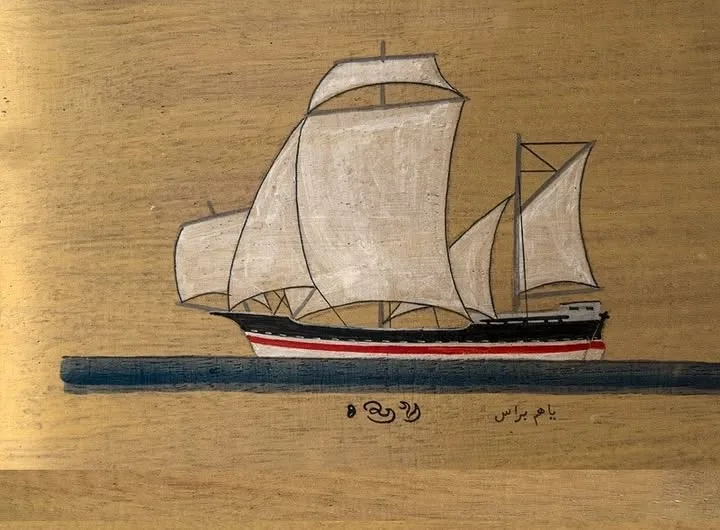

The veḍi (known as oḍi in the central atolls) was the largest traditional boat ever crafted in the Maldives, often reaching lengths of fourteen meters. What made these ships remarkable was not just their size, but their construction.

Unlike Western ships of the era, which relied on rigid frames and iron nails, the early veḍi was a stitched vessel. Maldivian shipwrights used coir rope—hand-spun from coconut husk—to lace timber planks together. This was a deliberate engineering choice: a stitched hull was flexible. When striking the heavy swells of the Indian Ocean, the ship would flex and “breathe” with the waves rather than snap under pressure. Even as metal tools were later introduced, this philosophy of flexibility remained at the heart of Maldivian boatbuilding.

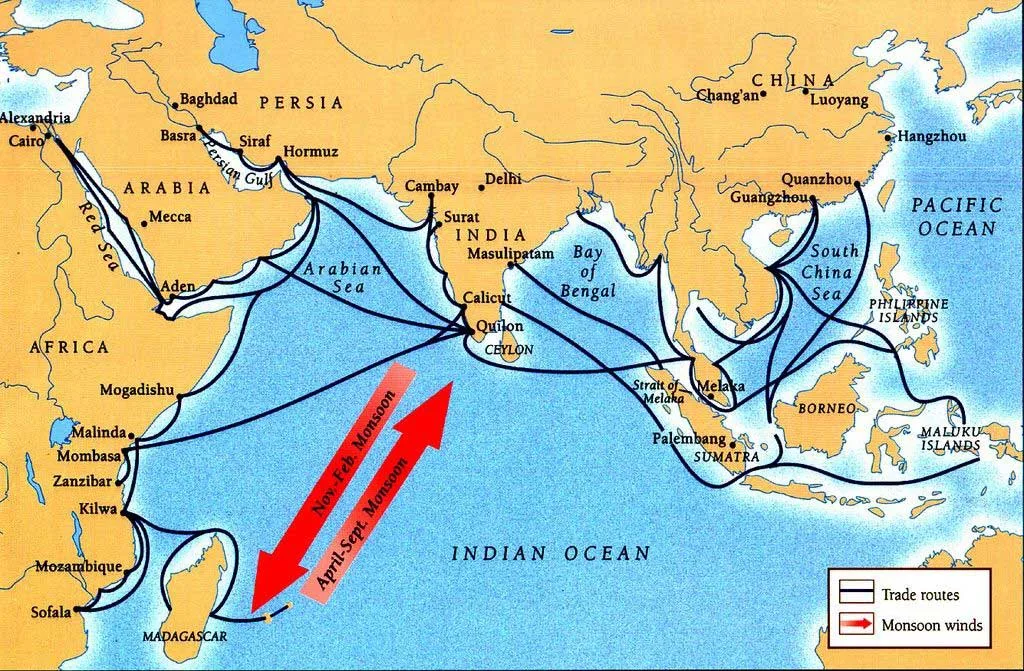

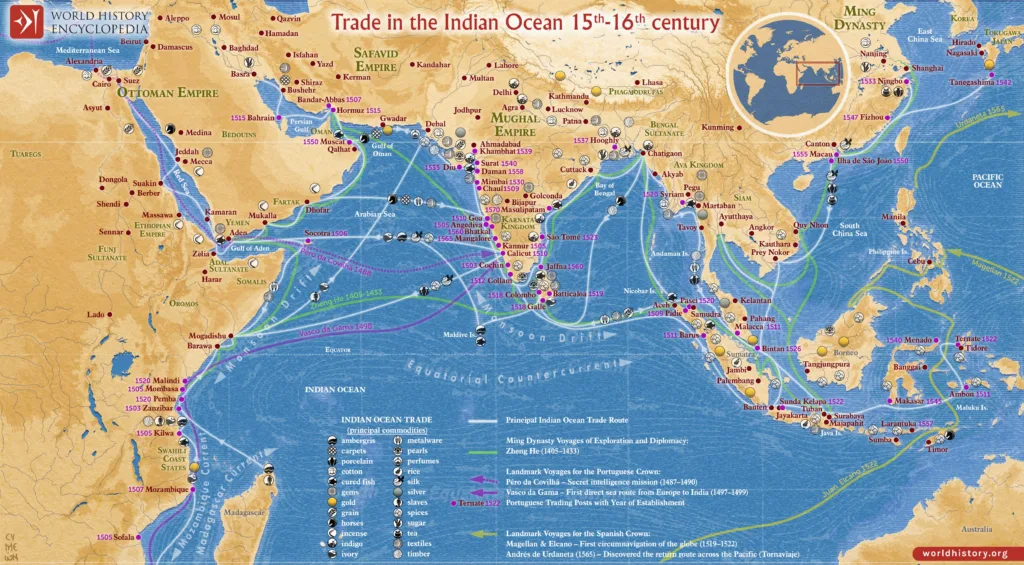

The Trade Routes: From Fuvahmulah to Ceylon

Each time a veḍi cleared the reef, it carried the economic hopes of an entire atoll. These were not leisure journeys; they were grueling, weeks-long missions to exchange island resources for basic necessities.

Navigating the “Invisible Islands”

| The Outbound Cargo | The Return Necessity |

|---|---|

| Dried Tuna (Hikimas): The primary export. | Rice & Grains: The staple diet not grown on atolls. |

| Coir Rope (Roanu): Famous for its strength. | Textiles: Cloth for clothing and sails. |

| Cowry Shells: Ancient currency of the ocean. | Metal Tools: Forged steel for carpentry and farming. |

| Ambergris: Rare finds used in perfumes. | Pottery: Essential for cooking and storage. |

The greatest challenge for a maalimee (navigator) was the nature of the Maldives itself. With no mountains and only low-lying land, the islands are virtually invisible at sea until a vessel is dangerously close to the reef. This led to the dreaded Sea’s Betrayal—the realization that a ship had sailed past the archipelago and into the vast emptiness of the southern ocean.

To counter this danger, veḍi crews relied on a living navigation tool: the frigate bird. These birds were kept aboard and released when sailors suspected land was near. Because frigate birds must return to land to roost, their flight paths served as a biological compass guiding sailors back toward the atolls. In some cases, a bird returning to land with a message tied to its leg was the only way an island community learned that a vessel was lost.

A Legacy in the Blood

For my family, the veḍi is not distant history—it is personal. My grandfather, Hussain Didi (Kudhubea) of Fuvahmulah, was among the master builders who understood the language of timber and rope. My late uncle, Ibrahim Didi (Beyappaa), lived the life of a maalimee, guiding these massive wooden vessels across the blur of the Indian Ocean using nothing but the stars and the seasonal monsoon winds.

By the mid-twentieth century, the rhythmic creak of the veḍi’s masts gave way to the thrum of diesel engines. Yet the spirit of the veḍi endures. It remains a reminder that the Maldives is a nation born of the reef—but sustained by the courage to sail beyond it.