How Maldivian words shaped the science of coral reefs

Long before scientists began charting the Maldives, the reefs already had names—names shaped by generations of navigation, fishing, and daily life at sea. When early marine researchers arrived in the archipelago, they encountered a seascape so intricate that European scientific vocabulary alone proved inadequate. To understand it, they turned to the language of the islands themselves.

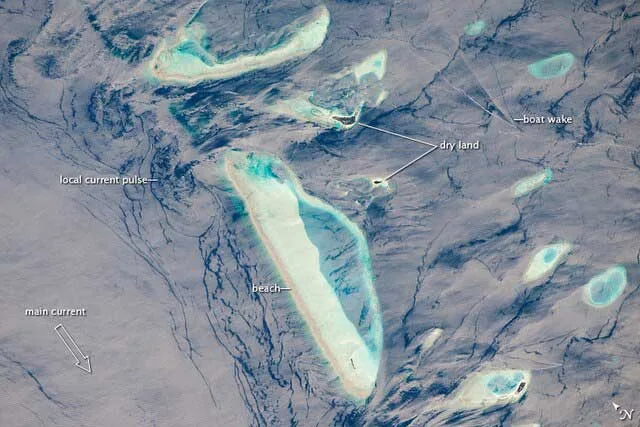

In The Coral Reefs of the Maldives, local Dhivehi terms quietly enter the scientific record. Among the most significant is faro, a word Maldivians use to describe small, ring-shaped reef structures that rise within lagoons or along reef rims. These formations did not fit neatly into Western categories such as “bank” or “atoll.” To islanders, however, their meaning was exact—defined by shape, depth, and position in relation to currents and land.

The adoption of faro was more than a linguistic convenience. It reflected an acknowledgment that Maldivians possessed a highly developed understanding of reef geography, refined through centuries of lived experience. For sailors navigating narrow channels, fishers reading subtle shifts in water colour, and communities building lives atop coral foundations, such distinctions were essential. Language functioned as a tool for survival—and, eventually, for science.

European researchers soon discovered that relying solely on imported terminology led to confusion. Reef systems in the Maldives are layered, composite, and constantly evolving. Indigenous vocabulary, by contrast, offered clarity. It described not only what a reef looked like, but how it functioned within a larger seascape. In this way, Dhivehi words carried ecological insight long before ecology emerged as a formal discipline.

This exchange reveals a rarely acknowledged dynamic in the history of science. While Western expeditions brought charts, instruments, and theories, they depended on local concepts to interpret what they observed. Maldivian environmental knowledge did not exist at the margins of scientific discovery—it actively shaped it. The reefs were not merely measured; they were understood through ideas already rooted in the islands.

Today, as scientists increasingly emphasize the value of Indigenous and place-based knowledge, the Maldives offer an early and compelling example of such collaboration. More than a century ago, Maldivian language helped define one of the world’s most complex coral systems, demonstrating that the first maps of nature are often written in the words of those who know it best.

For an island nation built on reefs, this legacy is more than historical. It is a reminder that language, landscape, and knowledge are inseparable—and that the sea has always spoken Dhivehi first.