In the Maldives, boatbuilding is not merely a craft—it is a form of knowledge shaped by wind, tide, and necessity. Scattered across the Indian Ocean, the islands have always depended on vessels capable of crossing open water, and nowhere is that dependence more clearly expressed than in the dhoni, the country’s traditional wooden boat.

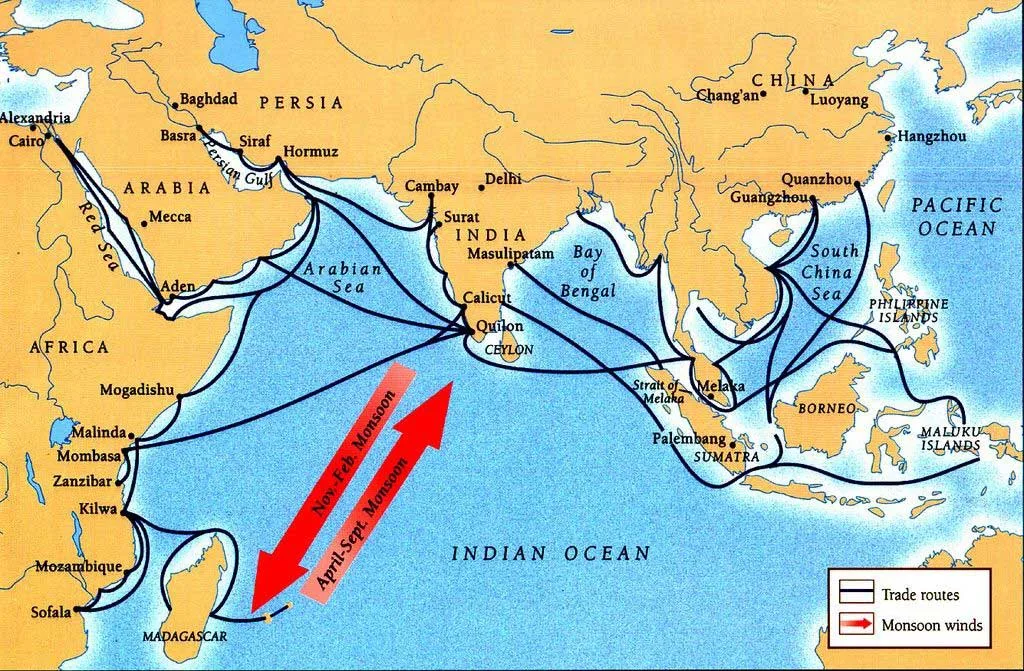

Long, narrow, and balanced, the dhoni carries a silhouette that feels both local and oceanic. Its graceful lines echo those of the Arabian dhow, a quiet reminder that the Maldives has long been part of a wider maritime world. For centuries, islanders have refined this vessel not through written plans, but through observation and experience, shaping a boat perfectly adapted to its environment.

Traditional dhonis were built without blueprints. Instead, a master carpenter—known locally as the maavadi—guided the process entirely by eye. Proportions, symmetry, and balance were judged instinctively, informed by years spent watching boats ride waves, carry loads, and survive storms. Knowledge passed from hand to hand, generation to generation, with little need for measurement beyond what the sea itself demanded.

Early dhonis were constructed almost entirely from the coconut palm, the most abundant resource on the islands. Timber formed the hull, while coir rope, twisted from coconut husks, bound the wooden planks together. Even today, the language of boatbuilding reflects this past: the Divehi word used to describe building a boat translates literally as “to tie.”

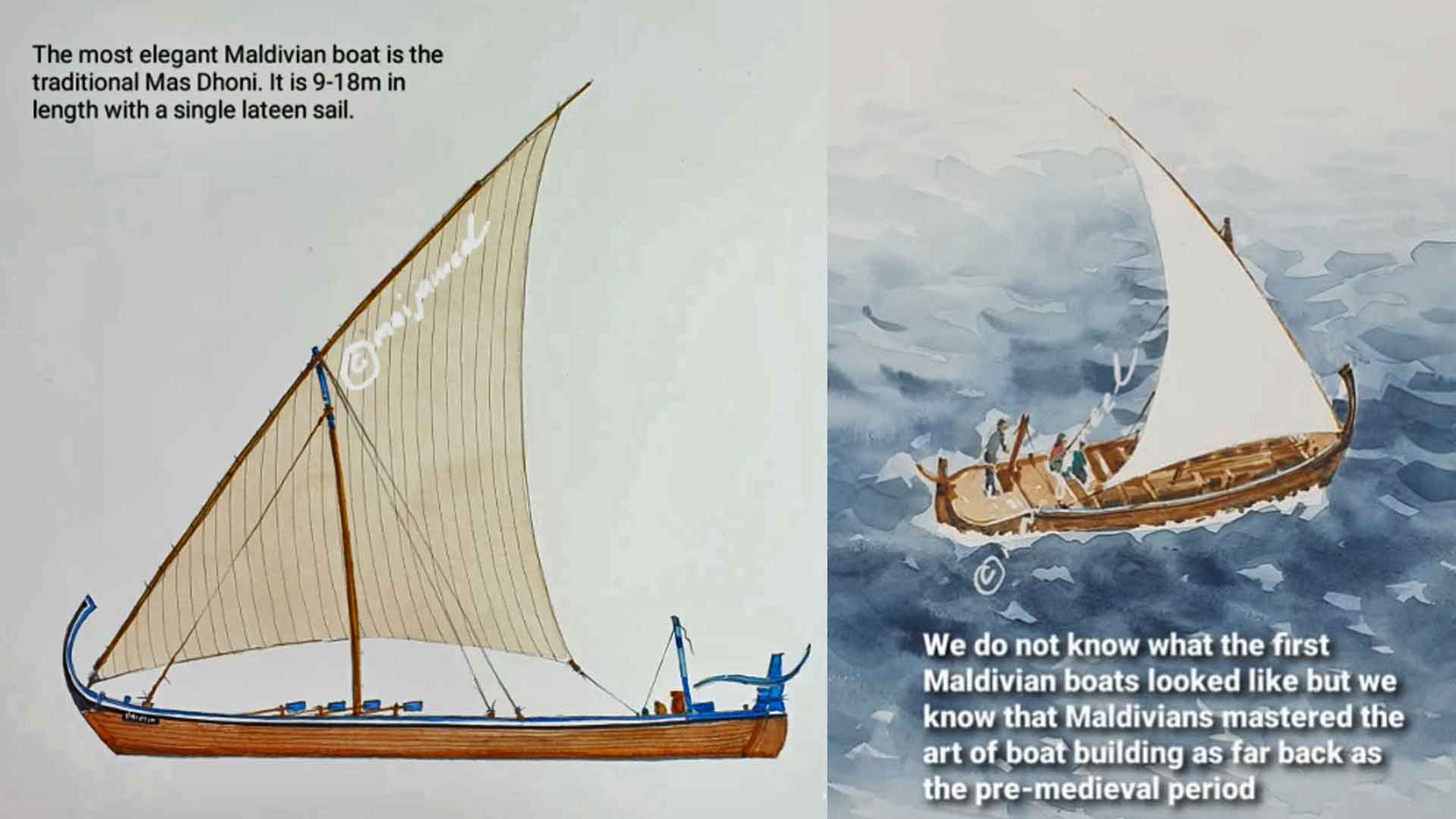

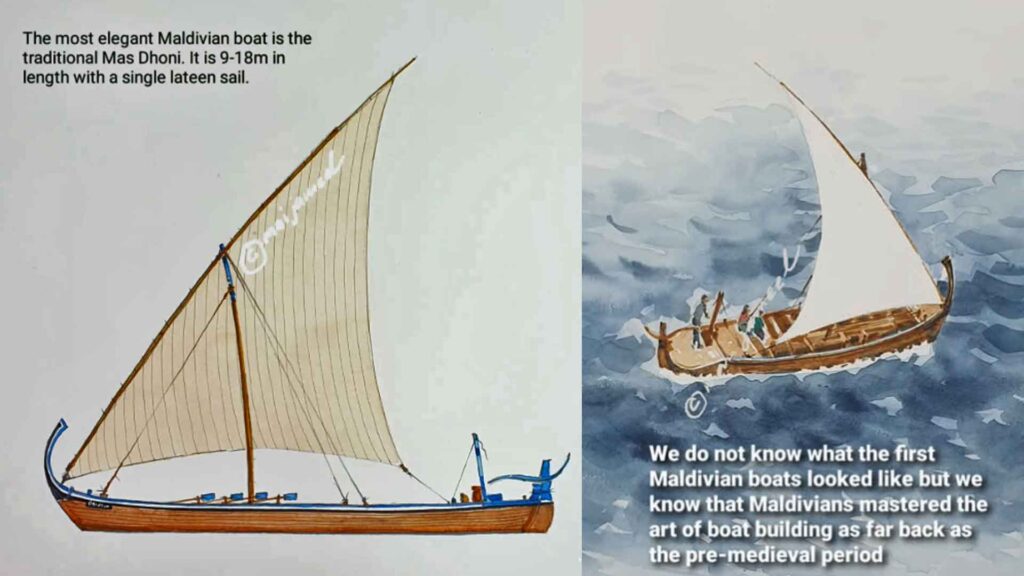

As trade and contact with other seafaring cultures increased, the dhoni evolved. Coir lashings were gradually replaced by wooden pegs and later metal fastenings, improving strength and durability. Imported hardwoods replaced coconut timber, and sails changed as well. Square sails woven from palm leaves gave way to triangular lateen sails, better suited to the shifting monsoon winds that govern life in the Indian Ocean.

Eventually, engines replaced sails as the primary means of propulsion. Yet many dhonis still carry sails today—not out of nostalgia, but as insurance. On the open ocean, redundancy is wisdom.

Despite these changes, the dhoni’s essential form has endured. Its balance, proportions, and seaworthiness remain largely unchanged, a testament to a design refined by centuries of trial rather than theory. This continuity reflects a deeper truth: in a country without natural harbors or protective lagoons, every boat must be capable of facing the open sea.

Today, dhonis ferry fishermen at dawn, carry supplies between islands, and glide across lagoons with travelers aboard. Their modern roles may differ, but their purpose remains the same. Each one is a living artifact—proof that in the Maldives, craftsmanship is not measured by ornament or complexity, but by how well a vessel reads the ocean.

In the end, the dhoni is more than a boat. It is a solution shaped by geography, a record of accumulated knowledge, and a quiet expression of how islanders have learned, over generations, to live with the sea rather than against it.

Further Reading:

Romero, J. The Maldives Islanders: A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Kingdom.